|

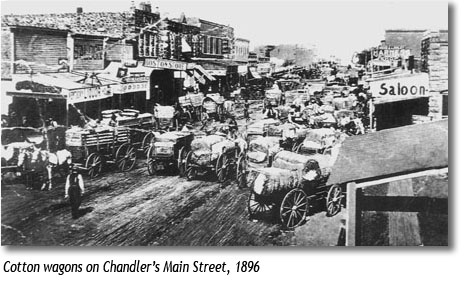

The state of Oklahoma is near center mass of the United States — bordered by Texas to the south and west, New Mexico to the west, Colorado to the northwest, Kansas and Missouri to the north, and Arkansas to the east. Prior to statehood in 1907, one half of the state belonging to several Indian tribes was called Indian Territory. The other part, mostly the western half, was called Oklahoma Territory and belonged to the United States. Because of its rough and rugged nature, early history books sometimes referred to the area as the “uninhabitable” part of the United States. On September 28, 1891, immediately after a land rush, Chandler was founded. In the land rush some 975,650 acres of land, formerly owned by the Sac and Fox, Iowa, Pottawatomie, and Shawnee Indian tribes, was divided among thousands of people participating in one of many land distributions in the Oklahoma Indian Territory. Originally, Chandler only comprised an area of about one square mile. The first plat divided the town east and west by numbered streets 1-15, and north and south by eleven named streets such as Manvel, Allison, and Steele Avenues (city map of Chandler can be found in Appendix A). Since Chandler's original founding, city boundaries have been extended several times. Despite the expansion, the majority of the residents still live within the original 1891 city boundaries. While there have been some variations, the population of Chandler has never gone above 3,000. The 1900 census recorded about 2,000 residents, and the one in 2000, almost 3,000 citizens. Chandler is a typical Oklahoma county seat. Manvel Avenue, a main street several blocks long, is the centerpiece of town (and is often referred to as “ Main Street” in our story. Most businesses, office buildings, and the county courthouse are located along Manvel Avenue. Residential housing extends outward for several blocks in all directions. Most residential homes were built on spacious lots, and during the first half of the 20th century colorful vegetable gardens filled their yards. Sometimes part of a yard would house a cow, chickens, or other livestock. Off to one side of the business area, one normally found a large agricultural facility such as a grain mill and elevator. As in many Oklahoma towns, business and agriculture co-existed in close quarters. In Chandler, the county courthouse was located near the center of town. My uncles recall one of its most amusing features. Before indoor plumbing and water fountains were established, a large, open barrel of public drinking water was maintained just inside the front entrance to the courthouse. A cup hung from each side of the barrel; one of the cups was clearly labeled, “For Colored Only.” After seeing people chewing tobacco and others with dirt-covered beards quenching their thirst, none of the Ellis family would drink from the barrel. Oklahoma towns are generally located on flat land, with unobstructed views in all directions. In this respect Chandler is quite different. The town is neatly perched on top of a large hill within which are a series of smaller hills. The town’s homes, stores, and buildings are scattered among the smaller hills. In some places, driving on city streets is like riding a roller coaster. “Bell Cow Creek” is a well-known local landmark, running west of Chandler, barely touching the western-most edge at Tilghman Park, and probably deriving its name from a cow. On farms a bell was hung around the neck of the cow that always started home first. This cow led the remainder of the herd back to the safety of the barn at the end of the day. The Ellis children and their friends, both black and white, spent many hot, happy summer hours swimming in the small reservoir created by the creek. In the Chandler area earth is reddish in color — not a true red, but a color similar to that found in bricks used to build houses. This special “flavor” of red colors the landscape with a dull building brick appearance. The red earth turns to a fine, irritating dust in the dry season. It is impossible to escape the red dust whipped about by small gusts of unexpected wind. Houses located near unpaved roads must be dusted two or three times a day. In the rainy season, the earth turns to red clay. In the old days, the heaviest rains came in May. From February to mid-June, at times it was barely possible to navigate the dirt roads of the county. Those who arrived in the city by horse and buggy were covered with red clay, their animals painted red from head to hoof. At the end of their journeys, those who walked the roads faced the time consuming task of cleaning thick red mud from their shoes and clothing. In the 1920s, and possibly earlier, to facilitate walking in the downtown area, wooden walkways were built in front of the stores and offices on Manvel Avenue. The wooden sidewalks resounded with “thuds” whenever someone walked on them. Imbedded in today’s cement sidewalks are some of the original horse rings used by cowboys, travelers, and everyday visitors to tie up their horses. Chandler’s special type of red earth was perfect for making bricks. Bricks made in Chandler were shipped all over the state. Before statehood, the bricks were stamped “OT,” for Oklahoma Territory. The few subsequently produced were stamped “Chandler, Okla.” Today, these bricks are sold as souvenirs and antiques. The wind and shifting red dust often hide vestiges of the past. Urban Green and his family were white residents who lived on a farm about 1½ miles north of Dudley, Oklahoma — about 18 miles northeast of Chandler. Urban recalls a happy childhood playing with the children of his black neighbors. He specifically recalls an old swimming hole just behind the family farmhouse. In the 1920-30s, many playful hours were spent jumping from a natural solid-rock platform into the water some seven or eight feet below. In the 1990s Urban returned to the old home site. The swimming hole and the rock platform were no longer visible. Over the period of 60 years, both the swimming hole and the natural rock platform had been completely swallowed by the wind-blown, shifting sand of Lincoln County. No early-day Chandler story is complete without some discussion of cotton. Almost every resident, black or white, was affected by the planting, caring for, and harvesting of cotton. Cotton had a significant economic impact on the citizens of Chandler and throughout the state. From the town’s founding in 1891, until the mid-1920s, the production of cotton and related activities were the most important sources of income for the town’s citizens. Cotton fields ringed the residential areas of Chandler. At harvest time, in the months of September and October, a white doughnut of cotton fields surrounded the large cluster of homes adjacent to the business district. Beginning at age six children learned to pick cotton, many continuing throughout their lives. Full attendance at school for older children could not be expected before mid-November, after the entire cotton crop was harvested. While both black and white residents worked in the cotton fields, the majority were black. Every Ellis child knew all aspects of picking cotton. Growing cotton requires several processes. The first was to plant the cottonseed in small furrows dug in the ground with hoes. In Chandler this furrow digging took place in late May. The second process was “chopping” cotton — when workers chopped the grass and weeds that continuously competed with the cotton plants. They also thinned out excessive cotton plants that could impair the crop’s quality. Chopping was difficult manual labor, but not the hardest task. The final process, picking cotton, was the most grueling. Almost all cash income for many families was earned during cotton-picking season. A skilled hand, working at full speed, could pick as much as 500 pounds in a 12-hour period. In the mid-1920s, a pound of cotton was worth about 50 cents to two dollars per 100 pounds. Prices varied depending on the quality of the cotton. In the early 1920s, because of severe droughts, damage from boll weevils, and other blights, cotton production was significantly reduced in Oklahoma. As a result, many “cotton picking” families were forced to temporarily relocate to simply earn a living. Entire families would go to other states for four or five months each year, returning at season’s end with their total cash income for the remainder of the year.

Each year, an award was given to the first planter presenting a bale of cotton to the local cotton mill. The award was given to encourage farmers to begin harvesting as early as possible, since the more cotton milled, the greater the profit for the cotton mill owner. A cottonseed oil factory was located at the end of Allison Avenue, where it meets 15th Street. Oil was made from the cottonseeds not used for planting the next year’s crop. Twice a day, at the change of work shifts, the cotton oil mill sounded a loud whistle at exactly 12 noon and 12 midnight. The sharp, shrill whistle could be heard cutting throughout the town. For many, it was their only clock. There are two transportation linkages of historic importance to Chandler: “Route 66” and the Frisco Railroad Line. Route 66 is a nationally known highway that runs down the main street of Chandler. Running through the middle of town, it brought a significant amount of commercial business as travelers crossed the state and the country. Entering Chandler from the west on 15th Street, Route 66 follows Manvel Avenue north to 5th Street. At 5th Street, Route 66 angles east and meets 1st Street. At 1st Street, it goes due east for 14 miles to Stroud, and then another 55 miles east to Tulsa. For many years, the Ozark Trail, as Route 66 was originally known, was a key road linking the West to Chicago. Beginning about 1950, section by section, a series of interstate and federal highways replaced Route 66. The Turner Turnpike now passes within a few hundred yards of Chandler's northern city limit. Opening May 16, 1953, the turnpike connected Oklahoma City with Tulsa making it unnecessary to enter Chandler when traveling through the middle of the state. Development of the turnpike was a major blow to the local economy and one of the reasons for lack of population growth in the last 50 years. Establishing the turnpike had a similar effect on many other small towns in Oklahoma, such as Kellyville, Bristow, Depew, Stroud, Davenport, Warwick, Wellston, Luther, and Arcadia. The other important transportation link, the Frisco Railroad, dissected Chandler from the northeast to the southwest. The railroad bed made a large “S” figure as it ran through the middle of town. Used only for freighting, the railroad bed is still in place. The last passenger train stopped running in 1974.

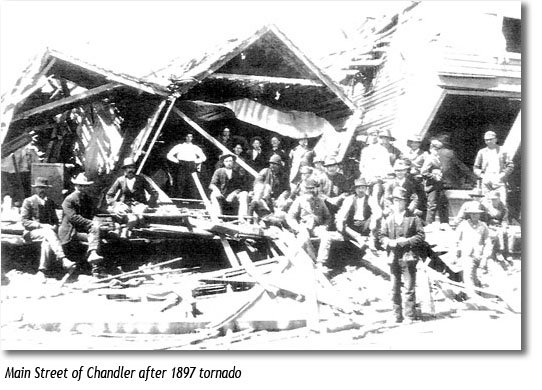

Two events affecting life in Chandler deserve special attention. After the September 22, 1891 land rush giving birth to Chandler, the small settlement became a boomtown. Local businesses developed along the main street for about four full blocks. This thriving business district included hotels, several saloons, stores, and other establishments. In 1897, a tornado completely wiped out the business area and many of the new homes constructed near it. The tornado was a traumatic event for James Riley and his family. The tornado struck several years after James and Ann Riley moved to the farmhouse a mile and a half from Chandler. Maggie Riley was only 17 years old at the time. Zodie, Polly and Winfield were all younger. The second event was the Depression of the late 1920s and early 30s, which will be discussed further in Chapter 4. Since the founding of Chandler in 1891, the number of black families living in the city has significantly fallen. The national census of 1900 recorded 2,024 persons living in Chandler; 52 black families, consisting of 274 people, were listed. In the 1996 Lincoln County census report, of the 877 blacks counted for Lincoln County, approximately 200 lived in Chandler. There are several possible explanations for the reduction in the city’s black population, all of which need further investigation. The first and most obvious explanation is availability of employment. Many black families depended on cotton as a major source of income. When the cotton crop declined, many families had to move to other areas to earn a living. The second explanation is a political one or one based on civil rights issues. The first state constitution in 1907 was amended to add a number of policies requiring segregation and restricting the ability of blacks to vote. The desire to avoid such laws in their previous home states was a major factor bringing hopeful black citizens to Oklahoma. Faced with repugnant, freedom-stifling laws of the new state constitution, they migrated again to other areas of the U.S. and Canada. SEGREGATION AND RACE RELATIONS While segregation and racism existed, in Chandler, its impact was significantly less as compared with all other parts of Lincoln county and the state of Oklahoma in general. Prior to 1940, 33 of Oklahoma ’s 77 counties did not have any black residents. Most of these all-white areas were located in the northwest part of the state. Chandler, like all towns in Oklahoma and most of the south, was segregated. In Chandler segregation was not as harsh as in other parts of the county and state. In the majority of contacts, whites and blacks were respectful. They often called each other “sir” or “ma’am.” My uncles recall their father always being addressed as “Mr. Ellis” or “Mr. Whit” by both black and white persons. Obviously there were exceptions to this compatibility. Some found it very difficult to extend these courtesies. Grandma Riley was called “Auntie” one time only! — this by a young white man who had just arrived from one of the deep-south states to start a new life in Chandler. On his first day of employment at one of the local stores, he made the deadly mistake. There was no need for the shop’s owner to correct the young man. Ann Riley took care of everything in two or three quick and well-aimed sentences. From then on the young man always referred to her as “Mrs. Riley.” During the first half of the 20th century, black and white children often played together in all parts of town. For example, highly contested football and baseball games were played on the spacious lawn of the county courthouse. Such games were much more predominant among the boys who moved from one area to another as they played baseball and other sports. Girls were not permitted to go far from home by themselves, so as a result, young girls had fewer contacts with children of other races. There were occasional racial incidents, but in general the black, white, and Indian citizens coexisted in a comfortable environment. While racial harmony existed in Chandler, a well-defined separation has always been in place. White, Indian, and black citizens maintained separate lives. Today, as in the past, the three groups attend to their own places of worship and participate in separate social activities. The town’s cemeteries have been integrated since 1954. However, only two whites (spouses of blacks) have been buried in the “black” cemetery (Clear View) and only two blacks have been buried in the “white” cemetery (Oak Park). Until about 1950, restaurants, public transportation, medical services, hotel accommodations, etc. were segregated. However, there were always exceptions. From the beginning of Chandler, and despite criticism from their neighbors, some white businesses disregarded segregation and served blacks and Indians, as well as Chandler’s white citizens. A.D. Wright’s drugstore was one example of equal treatment and service to all. A.D. Wright founded one of Chandler’s first businesses. His pharmacy was set up in a tent in downtown Chandler. At A.D. Wright’s drugstore, everyone was welcome to sit and eat in the front part of the facility. Black residents seldom took advantage of this opportunity because they did not feel comfortable in doing so. Dr. John Adams was a white doctor willing to make calls at the homes of black citizens. Dr. J. Paul Smith, another white physician, assisted with my birth and that of my brother Whit. We were born at the 12th Street Ellis house in the early 1940s. I was born with a life-threatening medical problem that could not be treated in Chandler. The nearest medical facility was in Oklahoma City. The main hospital there had several hundred beds, four of which were reserved for colored people. There was a long waiting list to use those four beds. Dr. Smith, through his personal contacts, made arrangements for my immediate hospitalization. The day after my birth I was rushed to the hospital and received a life-saving operation. Without Dr. Smith’s intervention, the operation would not have been impossible. Chandler’s first schools were integrated and jointly attended by Indians, blacks, and whites. Maggie Ellis completed grades one through eight in an integrated school. However, in 1907, under amendments to the first state constitution, Oklahoma state law required a segregated school system. Grandma Ellis openly expressed her feelings about the new constitution: “One day I was free and the next day I lost everything.” The Chandler school system was segregated until 1955, one year after the Brown versus the Board of Education court battle ended with the Supreme Court declaring segregation was unconstitutional. The remainder of the county watched the integration process at Chandler High School to learn how best to carry out this sensitive task. In some of the adjacent towns, because of resistance, integration took more than two years. Around World War I, there were attempts to expand a local Ku Klux Klan (KKK) organization. While there were a few shows of strength, with marches and night rides, the black community never considered the Chandler KKK particularly threatening. During a horseback ride of Klan members down the Main Street of town, a black observer recognized one of the masked marchers and shouted, “Mr. Gladson, what you got that sack over you head for? Everybody knows who you is!” Many times black residents were saddened to find their close white acquaintances, and other persons least expected, among the masked Klansmen. Ora Ellis’s first memory, as a four-year-old, was a night ride of Klansmen in 1919. He recalls the memory as terrifying: the horses and riders, by the light of torches, cast eerie shadows on the landscape as the hooded group rode down the middle of Manvel Avenue late one night. There was an interesting phenomenon about secrecy among Klansmen. The black citizens of Chandler knew the identity of Klansmen for one simple reason. They did much of the laundry in white homes! It was difficult for Klansmen to conceal their identity from those washing and ironing their clothes and white uniforms. There are no records of lynchings in Lincoln County. In other parts of the state, lynchings were not frequent but physical mistreatment of blacks was not uncommon. It should be noted, however, that perhaps the worst single act of domestic violence in the U.S. took place in Tulsa, Oklahoma during the summer of 1921. During the two days of whites assaulting and arsoning the black Tulsa neighborhood, over 300 black citizens were murdered, 800 people admitted to local hospitals for injuries, 35 city blocks composed of 1,256 residences were destroyed by fire, and nearly $2 million dollars (almost $17 million after adjustment for inflation) in property damage. While Chandler never had them, several nearby towns had “sundown to sunup” rules. The most common restriction was to forbid travel in certain parts of a town from sundown to sunrise or to banish blacks from being within the city limits after dark. There were such rules in other parts of the county, but never in Chandler. It was not until 1936, when the movie “Green Pastures” was shown in Chandler, that blacks were allowed, on a one-time basis, to attend a downtown theatre. During the showing of this movie, they were required to sit in the balcony section of the movie theatre. In the late 1930s, William Mingo, a County Agricultural Extension Agent, operated a small movie theatre located at the corner of Allison Avenue and 15th Streets. It was a crude, temporary facility made by placing planks over a large ditch running parallel to 15th Street. The movie served the black community on Friday and Saturday nights. Mingo sometimes showed movies in other parts of the county as well. In the early days of Chandler, local newspapers played a key role in maintaining segregation and reinforcing poor images of black people. White-owned papers, published in the late 1890s and early 1900s, almost never mentioned black citizens. I remember scanning the most popular county papers from 1897 to 1902 and finding only a few articles about black citizens. One was a short article about a member of the territorial legislature supporting a program to send all blacks back to Africa; a second article announced a new cream that could change skin pigmentation from black to white. The article suggested that this was the best way of solving the “problem” of being black. The publication of The Black Dispatch by Roscoe Dungee in 1914 and the Crisis in1917 by the NAACP were the first opportunities for positive media comments on the state’s black population. In many towns, the railroad tracks were a demarcation line separating black and white communities. This was not the case in Chandler. While there were concentrations of black residents in places such as the “Bottom,” both races lived in almost all parts the city. Appendix A is a map indicating the 1920-30s locations of some of the private homes and other places mentioned in our story. In 1908, Dr. Conrad was the first black doctor to arrive in Chandler. After a year or so, he moved to Guthrie, a more lucrative location. In 1923, Dr. Sanders, another black physician, set up shop in Chandler. Within four or five years, he moved his main office to Boley, where there were more patients. He returned to Chandler on weekends to provide services to the black community. The most common medical need in the black community was assistance with childbirth. In the early part of the century, a group of Chandler midwives — Mrs. Gates, Katie Neal, and Omega Thurman — largely handled this task. The Indians had special medical and school facilities on local reservations. The nearby Sac and Fox Indian Reservations’ health facilities often provided assistance to both Indian and black citizens. Because of this, it is not unusual for black residents to have birth certificates indicating Indian Reservation birth. One fall evening in 1940, Maggie Ellis, received an unexpected visit from Mrs. Clinton Goodberry, a nearby white neighbor. She also lived on 12th St. and was a close friend of Maggie Ellis and many other black community mothers. She quickly related a short, alarming story. The family of a local white girl was concerned about a too-friendly relationship developing between the youngest Ellis child and their teenage daughter. Suggestions were made that violence against George was a quick way to end the relationship. Within an hour of receiving this information, George Ellis, a senior at Douglass School, was on his way to Langston, Oklahoma, where he remained until finishing high school the following year. George Ellis later described his relationship with the white girl as nothing more than politely recognizing each other several times on Manvel Avenue., exchanging smiles and nothing more. He also thought that part of the problem was jealousy. He often drove Grandpa Riley’s automobile, which was a newer and much more luxurious model car than the one driven by the girl’s parents.

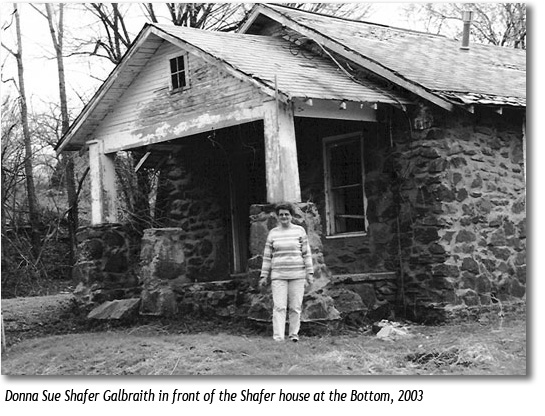

The “Bottom” was a nickname given to a one-block-wide housing area-extending north and south from 15th Street to 9th Street and east and west from Allison to Keokuk Streets. When standing on the front porch of the Ellis house on 12th Street, by looking south you can see the lower part of the Bottom. When standing at the southern end of the Bottom, looking north it appears that someone took a giant ice cream scoop of dirt from the earth’s surface. Perhaps, the impression left by the “giant scoop” was the basis for the name Bottom. It encompassed about 20 houses, several churches, and a cotton gin. While the Bottom housed people of both races, it was the city’s largest conclave of black residents. Ray Shafer and his family were one of two white families living in the Bottom. The second family was that of Mr. Ellis Jackson. The Jacksons had several children; one, Eileen, was a constant playmate of my mother, Ann. Donna Sue Shafer, Ray’s oldest daughter, describes a very normal and happy existence for her family. They enjoyed living in harmony with other Bottom residents. Donna Sue recalls many times being the only white face at Mingo’s movie house, also located in the Bottom. Ray Shafer ran a successful auto repair shop out of a garage built to the rear of their house. Ray built the house by himself. He personally hauled local rocks from several miles away to build the structure. His house construction was done in the evenings, after a full day of work at his shop. The house and garage still stand in the Bottom.

One terrible childhood memory haunts Donna Sue Shafer Galbraith. At a young age Donna Sue, her brother, two sisters, and three neighborhood children were playing in front of their house when a drunk driver lost control of her car and injured all of the children. The youngest Shafer daughter, two-year old Nita Rae, was killed. The Bottom was also the home of one of Chandler’s most famous smile makers — Ellis Charles, more commonly known as “Piggy.” Piggy was a very handsome man, as described by both women and men. Piggy Charles’ home was located directly across from Ray Shafer’s brick house and about one hundred meters northwest from Chandler’s railroad station. As far as anyone knows, Peggy’s father was a black man and his mother a full-blooded Creek Indian. Sarah, Piggy’s wife, was an unusually charming woman who worked as a cook. She was petite, standing about five feet, two inches, and known throughout the town for her hourglass figure and spotless appearance. She was never seen without a freshly pressed dress and neatly groomed hair. After working 12 hours in a hot kitchen, Sarah would return home with clothes neatly arranged and clean just as if she were starting the day. From Piggy’s house, the constant arrival and departure of trains could be heard throughout the day and into the night. The sounds became second nature to Bottom residents and presented no distraction.

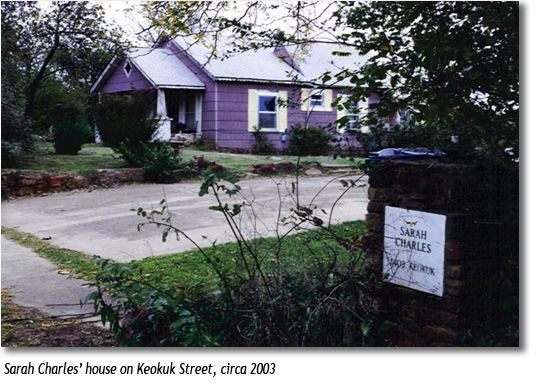

Piggy and his wife, Sarah, lived in the Bottom during the Depression. From the front room of his home, Piggy ran one of the county’s most famous “speakeasies.” A speakeasy was a place selling bootleg alcoholic beverages during the Prohibition Era. Speakeasies were small clubs, just one or two rooms, where dancing and card playing were common. Open until the early hours of the morning, they were hangouts for singles looking for “friends.” Many a night a wayward husband was dragged from Peggy's by his irate wife. Neighbors jokingly told of seeing Federal agents going in the front door of Piggy’s home as he quickly departed through the rear of the house, dumping bottles of “bootleg” whiskey as he ran. After living in the Bottom for many years, Sarah and Piggy purchased a home on Keokuk Avenue, only several hundred meters from their home in the Bottom. The house stands today, neat and tidy just like Sarah. Her name, Sarah Charles, remains engraved on the two corner posts on either side of the driveway entrance to the house.

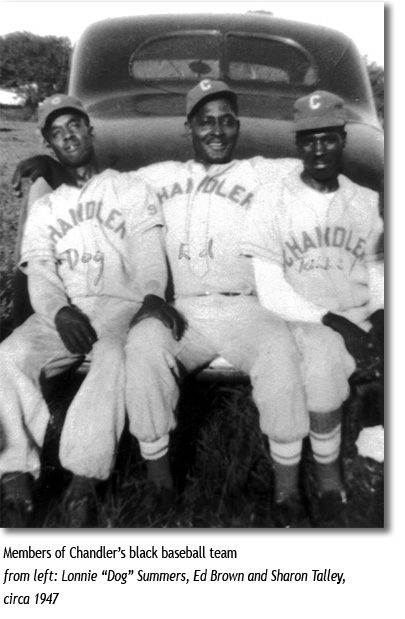

Piggy later became a constable and then a custodian at a local bank. He and Sarah never had children of their own but raised six of Piggy’s brothers’ and sisters’ children. Piggy died in 1957 and Sarah about 10 years later. They are buried side-by-side in Clear View Cemetery. Sarah’s grave remains without a headstone. Much has been written about America’s legendary black professional baseball leagues that flourished in the 1920s, 1930s, and early 1940s. Unfortunately, little has been recorded about the local amateur baseball organizations that served as an informal farm team system for the professional league. An excellent example of the farm team system was found in Chandler. In the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, playing baseball was one of the most popular spring and summertime activities. A large network of black professional teams played in small stadiums throughout Oklahoma, and an extensive amateur black baseball system was established. Teams in the amateur league played wherever space was available. This was often nothing more than a cow pasture borrowed from a local farmer. A white baseball team system was organized in Chandler sometime in the 1920s. It was not until 1930 that black teams began playing. They played on a field located in southwest Chandler 12th Street, where the street runs into Joe Long Avenue. At the age of twelve, Francis Ellis was the team’s first batboy. He served in that position until 1934, when he departed for studies at Langston University. He recalls many interesting stories about the team. As batboy, Francis traveled with the team throughout the state and sometimes into southern Kansas and northern Texas. Francis’s parents, Maggie and Whit, were acquainted with the team’s manager, Tom Black. Before allowing Francis to take the batboy position, Maggie had a private talk with Tom to ensure special attention would be given to their young son when the team was on the road. Tom promised Maggie he would serve as surrogate father when the team left Chandler. Between 1930 and 1933, the Chandler Team, as they were called, proved to be one of the best on the state “colored amateur baseball” circuit. While there were teams organized in almost every large black community, there were only 10 or 12 that were considered good teams. The Chandler team was one of the top teams in this elite group. Usually the top teams only played among themselves to ensure strong competition and big crowds.

Games were played on the weekends. The team was comprised of players from a wide range of ages; there were high school students and men in their 20s and 30s as well. Two of Ora Ellis’s classmates, Floyd Brown and Charleslo Williams, were on the team. There was no formal system for managing play between teams. All games were informally arranged between managers. Transportation was a major problem. Team member cars usually transported the team and its equipment. For nearby games it was not uncommon to arrive on a flat-bed truck. Riding over unpaved backwoods roads on a flatbed truck guaranteed half of the players started the game with multiple bruises covering much of the lower part of their bodies. A complete team consisted of 9-14 players, which resulted in some teams competing with only one player at each position. It also meant that each athlete had to play at several positions. Noted for strong hitters and excellent fielders, the Chandler team was a remarkable assortment of talented athletes. In addition to winning the ball game, a good team also had to entertain the crowd. Each team had one or two “clowns” to carry out this important task. The team clown would have a wide assortment of tricks. Almost every clown could perform two basic maneuvers. The first was to catch the ball and then immediately fall to the ground in the splits, one leg completely extended forward and the other in the opposite direction. The most talented clowns could immediately regain their footing with minimum use of their hands. The second move was done when catching a fly ball. The ball would land in the fielder’s glove and be immediately tossed 6-10 feet in the air. On the upswing journey, the clown would take off his hat and fan the air below the ball as it was on the rise, then replace the cap on his head and catch the ball before it landed on the ground. In 1933, Francis Ellis had the opportunity of a lifetime — to bat against the legendary Black Hall of Fame pitcher, LeRoy “Satchel” Paige of the Kansas City Monarchs. The Chandler team had been invited to play as the second attraction at a stadium hosting the Monarchs. The Monarchs was one of the top teams in the country and the featured attraction. They were scheduled to play against another professional team which was unable to appear. At the last minute, the Chandler Team was asked to substitute as the Monarchs’ opponent. Satchel Paige pitched, and his team quickly established a large lead, as was expected. Near the end of the ninth inning, for the sake of humor, Satchel boasted to the crowd that the Chandler team could even send in the batboy and he would also strike him out. The Chandler coach went along with the joke and told 15-year-old Francis to take his place in the batter’s box. Francis prepared to receive the first pitch. He was wearing his neatly pressed uniform with the words “Batboy” in big letters on the back (letters were cut out and sewn on by his older sister Roberta). Satchel waved for the other members of the Monarchs to leave the field: “I don’t need no help to take care of this little matter.” Francis took a warm-up swing with his bat. The crowd began to cheer for him. Satchel wound up and delivered one of his famous super spin pitches. The pitch had so much spin it gave the batter only one option – hit the ball with a short bounce that usually landed in Satchel’s glove outstretched in some comical fashion. Francis made a powerful swing at the ball and hit it solidly. The ball took the expected short bounce on the ground, landing about 15 feet in front of Satchel’s waiting glove. Instead of landing in “Satch’s” poised glove, it bounced about two feet over his head and continued into the outfield. Satchel Paige made no attempt to field the ball and applauded along with the shouting crowd as Francis quickly ran around the bases and touched home plate. The game ended soon after Francis’ home run. All members of the team returned to Chandler with a once-in-a-lifetime memory of playing against “Satch” and the great Monarchs. I have a lifetime legacy that my uncle “homered” off of the great Satchel Paige. It is my hope that this chapter has presented Chandler, not as a typical small town in Oklahoma, but one with some powerful differences in white community enlightenment toward their black neighbors, as shown by my family’s experiences. There are two very important observations on segregation. Despite this fairly compatible picture, among the black community there was deep, constant concern about what could occur if their white neighbors were aroused. Secondly, segregation initially denied black residents access to the same quality of resources and opportunities as their white neighbors. Unlike the situation in most other towns, in Chandler this disadvantage was converted to a positive force uniting the black community and motivating it to perform at a higher level. A key individual in this process was Mrs. L. Lena Sawner, Principal of Douglass School, whose contributions are discussed in Chapter 8.

|

||