|

From 1902-1934, Mrs. L. Lena Sawner was principal of the local separate educational faculty, Douglass School. Attending Douglass School was one of the most significant developmental events in the lives of the Ellis children. Seven of the 10 Ellises spent their entire primary and secondary school years (grades 1-12) at Douglass under Mrs. Sawner. The other three, spent at least half of their early educational careers at the school before Mrs. Sawner’s retirement in 1934.

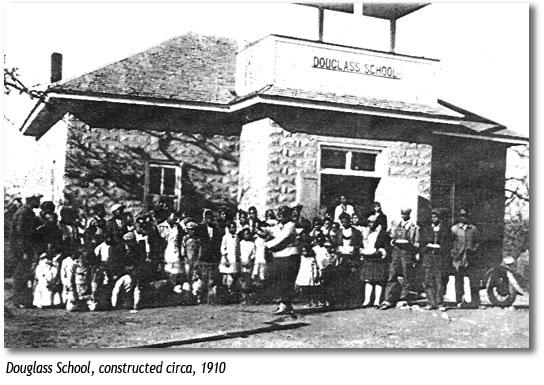

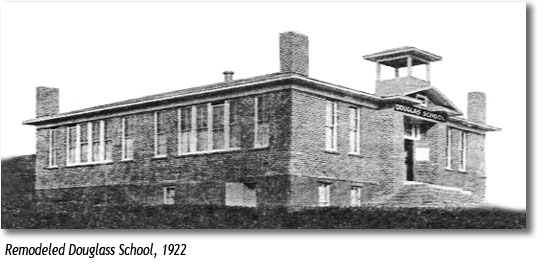

Douglass School has an interesting history. The earliest mention is in an 1896 local newspaper article mentioning Zodie and Pollie Riley, the daughters of James and Ann Riley, who attended Chandler Separate School and maintained perfect attendance. I believe the school mentioned in the article became Douglass School in 1902. Designation as a “separate” school indicated it was only for black children. It was also considered the central separate school in Lincoln County because it was the largest and most centrally located educational facility.

A November 6, 1908, article in the Chandler Publicist mentions Mrs. Sawner, principal of Douglass School, reporting a fire set by arsonist that destroyed the pine wood school structure. Mrs. Sawner commented, “A new and more commodious building would be constructed as soon as possible.”

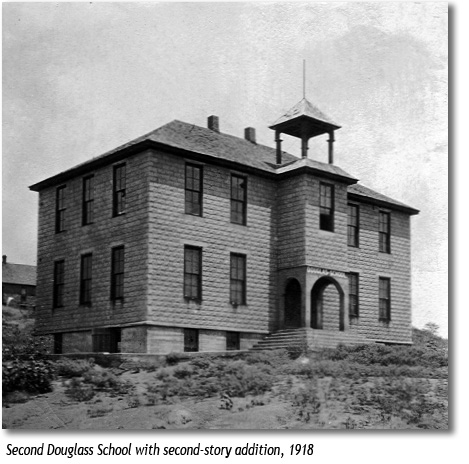

In 1910, a one-story, two-room brick school building was constructed to replace the one lost by fire. A second floor, with two additional rooms was added in 1918.

In 1922, the brick school building was torn down and replaced by a modern two-level brick structure to which a gym was added in 1927. Today, only the gym and several adjacent rooms remain. This complex is now called the “Douglass Community Center.” It provides a public place for local events such as meetings, social activities, funerals, and the annual reunion of the Douglass High School Alumni Association.

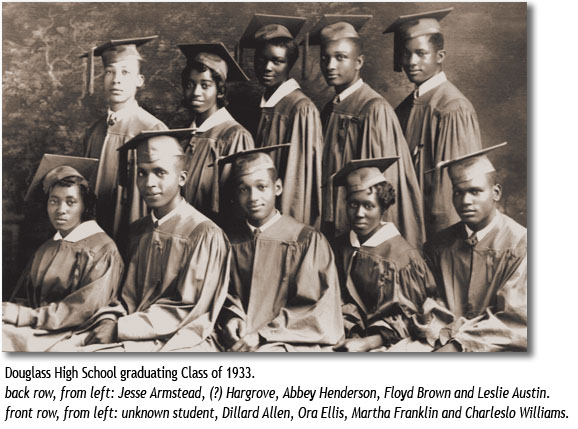

Initially Douglass School only provided education for grades one to eight. In 1911, grades nine to twelve were added. The first high school class of four students graduated in 1915.

In 1955, the county school system integrated and grades nine to twelve began attending nearby Chandler High School. Several years later the remaining grades were transferred to integrated schools and Douglass School, as an educational facility, closed its doors for the final time.

The Ellis family was a fixture at Douglass School. In every year between 1907 and 1940, at least one member of the Ellis family studied at Douglas School. In 1917, six Ellis children — Roberta, Whit, Cliff, Wade, Jim and Hasko — attended at the same time.

From 1922 to 1928, Roberta Ellis taught primary grades at Douglass, where the student body included several of her siblings.

Mrs. Sawner became a “virtual” member of the Ellis family, receiving total trust in assisting Maggie and Whit with rearing their large family. Mrs. Sawner had a similarly close relationship with nearly all black families with children attending Douglass School. The youngest Ellis child, George Sawner Ellis, is named after Lena’s husband, George W.F. Sawner.

For the Ellises, it was a perfect match, pairing the responsibilities of parents with those of the persons educating their children. Mrs. Sawner demanded the same values, behavior, and attitudes as were required at the Ellis home.

MR. AND MRS. GEORGE W. F. SAWNER: A NEW BREED OF PIONEERS

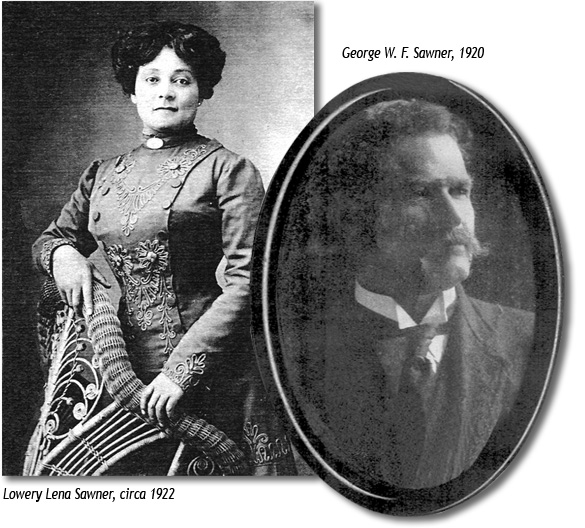

The Sawners were devoted Christians who believed in hard work and discipline. Their contributions to the Ellis family and to the state of Oklahoma are immeasurable. All evidence indicates that George and Lena were the first black couple active in statewide Oklahoma politics. From their 1903 marriage until George’s death in 1924, both of these leaders tirelessly worked to improve the status of Oklahoma’s black citizens.

In 1874, Lena Lowery was born in Richmond, Indiana. About 1902, she arrived in Chandler to become principal of Douglass School. At the time of her arrival, Lena’s parents were living in Newkirk, Oklahoma, about eight miles south of the Kansas border. They were influential members of Newkirk’s black community who owned a farm obtained during the land rush.

In 1860, George W. F. Sawner was born a slave in Mississippi. At an early age, he became a schoolteacher. In 1890 George arrived in Oklahoma and began working as a lawyer with the Sadler, Sawner and Twine firm in Guthrie Oklahoma. He also became a successful businessman purchasing and selling cotton and other commercial items. George owned valuable real estate in the Chandler area, and soon after his arrival in 1891, he became wealthy from the sale of commodities and land investments.

It is possible, but not certain, that in 1906, George Sawner, along with Edward McCabe and several other representatives of the Afro-America League, was selected to meet with the President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt. Their mission was to discourage the President from signing the new constitution for Oklahoma’s statehood. They were to express concern that the Constitution was a “Jim Crow” document severely limiting the rights of black citizens. It is not clear whether this exceptional meeting ever occurred.

Lena and George met in Chandler in 1902, the first year Mrs. Sawner was principal at Douglass School. They married the following year. For some unknown reason, after marriage Mrs. Sawner referred to herself as L. (Lowery) Lena Sawner instead of Lena Lowery Sawner.

The Sawners were extremely light-skinned and could have easily passed for white if they had desired to do so. They were in constant conflict with railroad conductors who demanded that they sit in the white section of the train and not in the less comfortable “Jim Crow” cars.

Lena Sawner was an immaculate dresser. She wore only the latest styles purchased at the most expensive stores. Mrs. Sawner boasted that the ostrich plume in one of her many hats cost $30.00. Additionally, she was seldom found without a small, gold-trimmed ivory broach delicately hanging around her neck.

In the mid-1930s, Mrs. Sawner joined an organization that subsequently adopted by-laws requiring members to wear black to their monthly meetings or pay a cash fine. Mrs. Sawner had always refused to wear black clothing. Instead, at the beginning of each meeting, she would politely place the fine on the table in front of the group’s board of directors. Dressed in her traditional brilliantly colored attire, she would quickly take a seat in the middle of the front row in clear view of those who had initiated the by-law.

Mrs. Sawner’s expensive clothes were always in sharp contrast to those worn by her poor black students. She was fond of the color purple. Some of her most stunning outfits are on display at the Museum of the Lincoln County Historical Society in Chandler.

Lena and George were very much in love. George died on May 1, 1924, and on every anniversary of his death, Lena printed his picture in the Black Dispatch newspaper. The picture was always accompanied by a short, romantic verse emphasizing how much she missed him.

MRS. LENA L. SAWNER: ONE OF OKLAHOMA’S UNSUNG HEROES

From the manner in which Mrs. Sawner immediately assumed charge of her duties at Douglass School, we believe she had prior experience and a strong formal education. James Ellis vividly remembers the diploma on her office read “Chi University.” We have tried to link the diploma with the University of Chicago, or any other institute, but have been unable to do so.

After arriving in Chandler in 1902, Mrs. Sawner spent the remainder of her life building the black educational system and helping to empower the black community — especially the youth. She was considered the senior teacher in Lincoln County’s “separate” school system and was often referred to as the Principal of the county’s separate school system.

MRS. SAWNER’S PRINCIPLES AND APPROACHES

Prior to 1927, the county allowed Mrs. Sawner to manage Douglass School independently. As a result, she initiated many creative approaches to education. Some 100 years later many of her approaches are considered cutting edge.

Initially Douglass School had no 11th grade. If they qualified to do so, students went from the 10th to 12th grade. Promotion was not automatic; very often, students were required to repeat a grade. It is believed that skipping the 11th grade was done because the accelerated pace of learning at Douglass School allowed students to learn more in less time. In 1927, when all county schools were required to follow newly established state educational guidelines and accreditation policies, this special initiative of Mrs. Sawner was discontinued.

Children normally started school at six or seven years of age. At Douglass School, age was not a criterion for beginning one’s education. The most important thing was whether or not the child was mature enough to learn. This initiative resulted in some children starting school as early as four years of age and graduating from high school before the age of 16. For example, Wade Ellis graduated from Douglass School at the age of 14 and from college at the age of 18. Roberta also began her studies at the age of four, as probably did several other members of the Ellis family.

- Anyone can learn if they apply themselves. This was Mrs. Sawner’s most important concept. If properly led, there is no reason for students not to apply themselves. This approach placed responsibility on both teachers and students to do their best. This principle was supported by zero tolerance for students who didn’t apply themselves and teachers who did not lead.

Unless there was a specific reason, such as marriage, illness, or the absolute need to work full time, Mrs. Sawner demanded that every student graduate from high school. She personally enforced this rule. Whenever a student was absent without an explanation, she visited their home to find out details of the absence. This usually resulted in the student returning to school the next day.

Based on interviews with Douglass School graduates, we estimate that more than 90% of students entering the ninth grade eventually (some had to repeat grades) graduated from high school. The data provided below for freshman classes was obtained from the following listed graduate:

Class of 1923: Maedella Summers Boone and 7 classmates started as freshman in 1919. All graduated.

Class of 1927: Jim Ellis and 11 classmates started as freshmen in 1923. All graduated.

Class of 1933: Ora Ellis and 16 classmates started as freshmen in 1929. All graduated.

Class of 1934: Francis Ellis and 10 classmates started as freshmen in 1930. All but one graduated.

Class of 1941: George Ellis and 15 classmates started studies in 1937. All graduated.

Class of 1943: Imogene Randolph and 15 classmates started studies in 1939. All graduated.

While some of the above students graduated after Mrs. Sawner’s retirement in 1933, they all spent time under her care and benefited by the creative educational system she established at Douglass School.

Additionally, it appears that as many as 25% of Douglass School graduates (after 1923) also graduated from college. Although these figures may not be entirely reliable, they are based on details supported by a number of Douglass School alumni who could comment on this area.

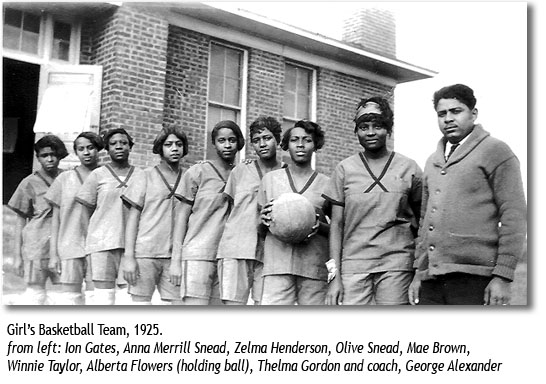

- The school must provide an holistic learning experience preparing the student for adulthood. The learning experience should not focus only on academic areas — social and other skills must be learned as well. Under Mrs. Sawner’s creative tutelage, every black child was exposed to a positive instructional environment and presented with the best educational resources available at the time. Graduating students were not only academically prepared, but they also possessed the social skills, determination, and confidence necessary to move ahead in a competitive world.

School began sharply at 8:45 every morning. Students in attendance were present for the school assembly where they recited the Pledge of Allegiance and read passages from the Bible. Mrs. Sawner and the other teachers discussed the day’s events.

Dances and other social events were organized — not just to provide fun, but taught social roles and rules for interacting with the opposite sex. In separate sessions for boys and girls, health, hygiene, and other sensitive issues were discussed. These controversial sessions and the social events created a stir with some black parents. A small group felt they were too risqué for the time. In 1927, these parents decided to start their own school. It only functioned for one year; parents then returned their children to learn under Mrs. Sawner’s contemporary approach.

- Black pride is a cornerstone for teaching black students. Mrs. Sawner believed that, “Everyone should always hold their head high and be proud of themselves.” Teaching students to be proud of their black heritage was one of her most honored objectives. Pictures of black leaders and their inspirational quotations covered the walls of each school room. Mrs. Sawner emphasized that being black was never justification for poor performance. Segregation placed enormous barriers in the paths of black children, giving them little incentive to improve themselves. This situation fostered a tendency of black citizens blaming others for their shortcomings. Mrs. Sawner focused on giving black children a better understanding of racism and her belief that high academic performance, self-respect, competitiveness, and determination could overcome it. Mrs. Sawner demanded that her students perform better than the white students who attended schools with much greater resources.

Information on successful black Americans, who overcame the inequities imposed on black Americans by segregation, were present in every corner of the school. Current copies of NAACP's (the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) magazine, The Crisis, and The Black Dispatch (the most popular regional black newspaper published in Oklahoma City) were always on hand. The National Negro Yearbook, Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery, and other such works, could be found in the small school library.

Mrs. Sawner believed it was important for students to have contact with positive black role models. Such contact created positive images and motivated students to establish higher goals and objectives for themselves. Positive role models started in the school with Mrs. Sawner and her teachers. As a teacher, Mrs. Sawner was a near perfect role model. Her diction and use of the English language were flawless. She walked in a proud and dignified manner, becoming the center of attention whenever she entered a room. The female students admired the expensive Parisian perfume she always wore.

An excellent public relations person, Mrs. Sawner traveled throughout the United States and became acquainted with many influential black leaders. There was a constant parade of black role model dignitaries visiting the school. Many were from the local area, but others were national level VIPs. Oscar De Priest, the first African-American elected to the United States House of Representatives in the twentieth century and the most well known black politician of that era; Roscoe Dunjee, editor of The Black Dispatch; Thurgood Marshall, NACCP General Counsel who later became our nation’s first African-American Supreme Court Justice; and many other black role models visited the school. The visitors reminded students that success was always at the end of hard work, honesty, and dedication.

- The local community and the school system must work together. Mrs. Sawner and all of the Douglass school teachers maintained close contact with the local community. Long before Hillary Clinton penned her book, Mrs. Sawner believed in the African proverb that, “It takes a village to raise a child.” Most teachers were single women from distant areas who were housed with local families. This provided them with close bonds with students and their families. Over the years several teachers stayed at the Ellis home. One of them, Irma Walker, eventually became the wife of James Ellis.

Teachers were required to monitor student progress carefully, both inside and beyond the school's perimeter. Within one semester of being hired, each teacher was required to visit the home of the students they taught. This further strengthened their relationships with the local community.

White children and adults sometime harassed Douglass School students as they walked home after school. When such problems arose, at the end of the school day Mrs. Sawner would be seen at the head of a long line of Douglass School children, personally escorting them down Main Street to ensure there would be no further problems.

Mrs. Sawner spent a great deal of her personal money supporting the school and the black community. Every Christmas season, she would take a small group of older students to Oklahoma City to buy every child a Christmas gift. She showed the same charity in the purchase of materials for the school. Many of the books and much of the materials used at the school were provided from Mrs. Sawner’s personal funds. She was also concerned about the elderly and often brought Thanksgiving and Christmas dinner to those who were homebound.

- It is important for students to compete. It is important that every child be competitive. Competition provides an opportunity to recognize and reward high achievers. It’s also a device for motivating those performing at less than their potential.

Annual academic and athletic competitions for grades six to twelve were held at Douglass School. Mrs. Sawner created the contests to motivate students to perform at their optimum and to reward high performers. During this two-day event, held on Friday and Saturday, competition was open to all black children attending Lincoln County schools. Typically, more than 200 hundred children participated. The school awarded grade level prizes to winners in categories such as athletics, math, civics, science, geography, Oklahoma and U.S. history, penmanship, English, and similar academic studies.

A group of students desired to have a school band. In 1927, Mrs. Sawner organized a cotton-picking event to raise money to buy instruments for the band. Students and teachers took three days off from school to pick cotton, the earnings were used to purchase instruments. Activities of this nature were done on a regular basis to earn money to support school activities.

- Teachers must be motivated and highly qualified. Mrs. Sawner carefully selected each teacher to ensure they possessed the required dedication and leadership skills. It was very rare to see teachers at Douglass School having less knowledge than the students they taught. This was not always the case in other schools. Mrs. Sawner maintained close contact with black colleges in Oklahoma and the adjacent states which facilitated the hiring of qualified teachers. She was well known for her ability to lure the “brightest of the bright” graduating college seniors to teach at Douglass School. In addition to hiring the most qualified teachers, Mrs. Sawner tended to select young, attractive, single women to teach at Douglass School. Many of them were very fair skinned like Mrs. Sawner. The attractive faculty may have been one of the reasons she was able to recruit so many VIPs to visit her small school in rural Oklahoma.

MRS. SAWNER: OKLAHOMA EDUCATIONAL PIONEER

In addition to the things previously mentioned, Mrs. Sawner made a number of other noteworthy achievements.

Douglass School was the first county school to provide free adult education classes. Mrs. Sawner and her staff taught basic literacy, free of charge. The classes were held in the evenings.

Mrs. Sawner was a founding member of the Oklahoma Association of Negro Teachers. The mission of the association was to play a leadership role in improving the quality of educators teaching black students. During her long career, it is believed Mrs. Sawner held every senior position in this dynamic organization.

In approximately 1916, the state of Oklahoma began accrediting schools. Douglass was one of the first six black schools to be state certified.

THE MOST INFLUENTIAL MEMBERS OF THE COMMUNITY

Churches and the clergy were a strong unifying force. For pioneers arriving in Oklahoma, the priorities were clear. The first task was to find food and shelter, and immediately after that, a place to worship. Church leaders, especially preachers, were some of the most respected members of the community. They often served as spokesmen to the outside world. The preacher’s Sunday dinner visit is an indelible image in the memory of black pioneer children. Only after the reverend finished eating and sharing his words of wisdom were younger family members served. Despite all this, teachers, not clergy, were the most influential members of the local community.

There are several reasons for this. Few preachers worked full-time at religious matters. Most were part-time clergy, earning their principal living by farming. Equally important, preachers did not live in the communities they served. In most cases, only twice a month did they visit to hold church services. These short contacts did not allow time for involvement in the day-to-day lives of parishioners.

The opposite was the case with teachers. Most teachers lived with families of their students and were available to assist with needs twenty-four hours a day. To illustrate further, while gathering information for both Chandler: The Ellis Family Story and The Negro Problem in Lincoln County, Oklahoma, more than sixty persons 75 years and older were interviewed. Only during one or two interviews were the names of preachers mentioned. It was the opposite with teachers. They were frequently recalled by almost everyone.

THE DEATHS OF GEORGE AND LENA SAWNER

George Sawner died in 1924 and Lena twenty five years later, in 1949. They are buried in the well-kept family plot of Lena’s parents in Newkirk, Oklahoma’s town cemetery. Many of the residents of Chandler think it is a shame they weren’t buried in their real home — Chandler.

The funerals of Lena and George Sawner were memorable occasions. Comments on their lives came from both the white and black communities. Both were given credit for improving relations between the two groups. At the death of George in 1924, all businesses in Boley, Oklahoma closed for one day. The Black Dispatch newspaper printed almost a full page of articles and comments about his life and his impact on the community he loyally served.

In 1999, I visited the gravesite of Mrs. Sawner and her husband in Newkirk, Oklahoma. It is a sacred place for two very special people. In a moment of silence, as I stared at Mrs. Sawner’s tombstone, I could not help but see her standing at the head of a room packed with all the students she taught and the teachers who worked with her over the years. She was talking with the group in her low and gentle voice. Gradually, everyone in the room raised their hands and smiled. There was a sea of eager faces wanting to be recognized — something very familiar to Mrs. Sawner. Everyone wanted to thank her for being an important part of their lives.

Lena Sawner’s impact on Oklahoma history is still unrecognized. During her 31-year tenure as principal, more than 200 well-educated black children graduated from Douglass High School. Our limited evidence indicates more than 90% of students reaching the ninth grade graduated from high school.

All ten Ellis children benefited from Mrs. Sawner’s special way of teaching children. She played an important role in their lives, requiring use of their full potential in every task they faced, being proud of their black heritage, and demanding they both gave and received respect.

Equally important, the Ellis children lived in a home environment full of motivation and encouragement. Many of Chandler’s children did not have this advantage. Mrs. Sawner was their only guiding light.

Douglass High School was closed in 1955. More than 50 years later, the Douglass School Alumni Association proudly holds its annual reunion at the site of the old school. It is a continuous reminder of the influential role Mrs. Sawner played in the lives of everyone she touched.

Much more research is necessary to fully appreciate the contributions made by Lena and her husband, George W. F. Sawner, to the development of Oklahoma.

|

|