|

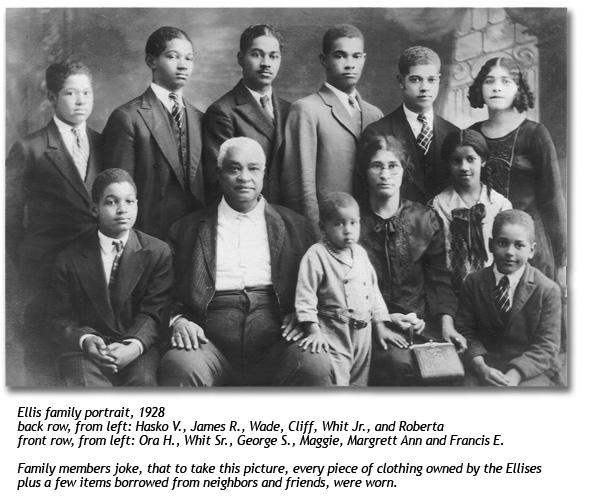

The family portrait above was taken at Christmas in 1928. The one missing person is “Baby Ellis,” who died at six months of age in 1903. To take the picture, the family walked several blocks to the photographer’s studio on Manvel Avenue. The parade of well-dressed Ellises caused quite a commotion. Heads were popping out of every store wondering, “What in the world is going on?”

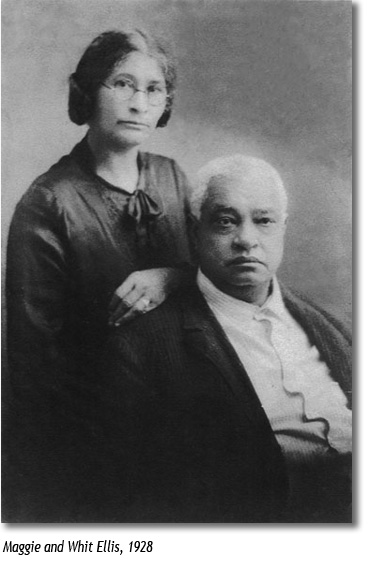

A quick glance at the photo above confirms that there is no standard Ellis look. Maggie Ellis had all the features of an American Indian: light brown skin, long, jet-black hair, high cheekbones, and a “sculpted nose.” Three Ellis children — Roberta, Whit Jr., and Hasko — were fair-skinned with dark red hair. Hasko had freckles. Wade could easily be mistaken for as South Asian. Other family members displayed a wide variety of physical characteristics. Some family members suggest the Ellises had Indian blood. That may be possible; however, our research has found nothing to support this. In the above photo, Whit weighed about 300 pounds and was twice the size of his largest child. Two characteristics became apparent as the children grew older: they were creative and quite skillful with their hands. The boys became excellent carpenters, builders, and improvisers. The two girls developed into talented cooks and seamstresses, skills that would often be called upon in their later lives. My mother, Ann, and her sister, Roberta, were renowned for their ability to cook gourmet meals with a Southern twist. My mother later became a dietitian, her concerns turning to health foods and how they could be used to improve health and control weight. At a young age Roberta became a cook in the Ellis restaurant. She could also sew just about anything. One of her most unusual triumphs was making a dress for a Douglass School play. The dress was crafted from paper maché and worn by Isadora Booker in a 1922 Douglass School production.

In general, Ellis family members were outgoing. They enjoyed being around other people, especially friends and relatives. Joking and having fun were an important part of their lives. The one exception was Cliff, an introvert. He avoided people, excitement, and being photographed. When Cliff’s fiancée, Minnie Argrove, talked with Maggie Ellis about her upcoming marriage, she was warned, “You are marrying my peculiar son.” Cliff had a brilliant mind and enjoyed wearing coveralls or old and out-of-style clothes wherever he traveled. He and Wade were very close and shared a deep-seated love for mathematics. Despite Wade’s outstanding academic achievements, he’d readily admit Cliff was the smarter of the two. In 1937, during the middle of the Depression, four Ellis children were planning to attend Langston University. At the beginning of the school year, Maggie Ellis met with the group and explained that the family did not have the resources to send all four children to Langston at the same time. It was Cliff who quickly volunteered to drop out of school and continue his education at a later date. All of the Ellis boys were skilled carpenters, and throughout their lives did all the carpentry work in their own homes. They were often found at the homes of friends and neighbors, helping them repair and build things. Francis, Hasko, and Ora remodeled and added rooms to the homes they bought after marriage. In 1956, Wade and his sons, Wade Jr. (“Butch”) and Bill, ages 15 and 17, completely built an ultramodern family home in Oberlin, Ohio while Wade Sr. was working at Oberlin College as a math professor. The home building project took every minute of their spare time for two years. In the mid-1920s, Jim Ellis used a mail order kit to build one of Chandler’s first radios. The radio was constructed on a board with all the parts visible. A large megaphone cylinder provided the sound. After this success, Jim was able to earn extra money by repairing the radios of other families in Chandler. Several years later, at the Riley farm, Jim made a windmill that provided electricity to power Grandma Riley’s radio. This made it possible for her to stay at home to listen to her favorite radio program, The Amos ‘n Andy Show. Without electric power, someone had to drive her into town once a week to hear the show. With the exception of Roberta and George, every Ellis child learned to play one or more musical instruments. In the mid-1930s, the family formed a band featuring Wade on the trombone, Francis on saxophone, Ora on coronet, Ann on the piano, James strumming the banjo, and Cliff on the bass drum. They played for their own enjoyment. Although on several occasions the band was asked to play at special functions, Maggie Ellis did not allow this. She was concerned that her young daughter, Ann, would be exposed to some of the “rowdy” elements who frequented the local party scene.

Although the Ellis children did not conform to any one physical or personality type, they developed uniform approaches to the everyday challenges of life. This is traced back to the clear and consistent guidance received from Whit Ellis, Maggie Ellis, Ann Riley, James Riley, Mrs. L. Lena Sawner, and a few other key persons. By far, Maggie Ellis was the most dominant influence in developing these uniform approaches.

The following is extracted from a six-page summary of the Ellis family history written by Wade Ellis in 1977. Prior to the current effort, it is the only known written history of the Ellis family. It provides an insider’s view of the principles most important to Maggie and Whit as they raised their family:

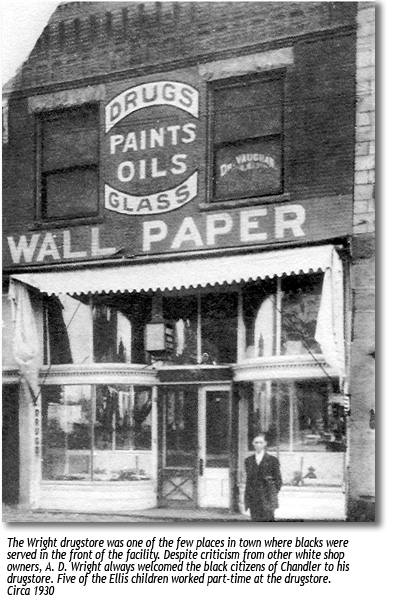

“The principles under which Whit and Maggie reared their children were greatly influenced by the 10 Commandments. When violated, they were strongly enforced with consistency and love. Honesty, discipline, self-respect and respect of others, were central. Lies were never tolerated and when discovered, punishment was swift, sure and imposing. Emphasis was placed on the harm done to one’s self as well as to others who might be affected. Each child was taught the value of hard work. The status of your work did not matter. What was important was how well you did the task and how wisely and effectively it was accomplished. There was honor in both physical and mental efforts. Courtesy and respect were extended and expected in return. A high degree of self-respect was a natural result from these guidelines. Self-development was also of major concern. A focal point was doing well in school. Whit and Maggie demanded their children do well in school. In the home, they encouraged discussion of schoolwork as well as interesting topics not covered in school. Maggie and Whit Ellis provided books, maps, and encyclopedias. Their library, both on the shelves and scattered around the house, contained a greater variety of books than any other in town — including the school and public library.” To further analyze Maggie and Whit’s key family principles, let’s modernize our discussion by calling them “core values.” Core values formed the heart of the special way the Ellis family dealt with the problems and challenges in the world around them. They were never written down, but every child understood them and how they should be utilized. The core values were general in nature, leaving a great deal of room for creative and individualized approaches to solving problems: 1. Belief in God is the cornerstone for a successful human being. The belief in God and following the 10 Commandments was a strong and omnipotent factor in the Ellis household. Each day family was reminded of their special relationship with God. The family bible was always visible. The only time it left the house was on its weekly voyage to church. At least two or three times a day someone would read passages from it. Despite strict reverence to God and the 10 Commandments, religion was seldom the topic of household conversation. It was a personal thing; something you believed but did not need to share openly with family, friends and neighbors. What you did, and not what you said, was an indicator of your religious commitment. In 1911, James Riley was a deacon and founding member of the Calvary Baptist Church. The church is still located on the corner of 12th and Bennett Streets. James Riley’s name can still be seen on the plaque in front of the church, commemorating its founding. In 1927, the Ellis family and several other families had a dispute with the church’s preacher about who owned the church. As a result, they changed their religious association to the Central Baptist Church, located adjacent to Douglass School. To this day, the Ellises are associated with that same denomination. Two of the church’s pews have Ellis and Riley family memorial plaques. They recognize James Riley, his grandson, A. W. Echols, and the Ellis family. Attendance at church was a must. Maggie Ellis was the one family member who occasionally missed the weekly walk to Central Baptist Church, this only happended when the chores of tending to her large family and helping out at the restaurant overwhelmed her. The church was the center of many activities. As mentioned in an earlier chapter, Ann Riley was frequently involved. The family bible, which we still have, was always accessible on a small desk in the family living room. To this day, this most cherished possession is rotated among the surviving Ellis children. The bible was not only a religious reference but it recorded the official names, birth, and death dates of family members as well. Before the advent of modern record keeping, the bible was an official legal document. In the early 1940s, Jim Ellis attempted to obtain social security numbers for his brothers and sisters. None had birth certificates, so to obtain certificates, the State of Oklahoma required the original birth date page of the bible as official verification of birth. There is another important reason that the bible was considered an official document. It was the one place the official name of each family member could be found. People often changed or modified their names. Grandma Riley used several first names such as Ann, Anna, and Annie. Grandpa Whit’s name in the 1880 Alabama State census was listed as “Whitfield Washington,” which he changed to Whit Ellis. His last name was probably changed after the fatal incident with the two white men when he was 14 years old. We believe he changed his first name from “Whitfield” to “Whit” when he married Maggie in 1900. The 1921 Langston University yearbook, The Langstonian, shows a picture of Roberta “Glendola” Ellis. This is the first and only document showing that name for her. Jim Ellis explains, “Roberta temporarily renamed herself.” My mother’s name was originally Margaret Amanda Ann Ellis. Sometime later, she became “Margrett” Ann Ellis, changing the spelling of her first name and dropping the name, “Amanda.” Amanda was the first name of her father’s mother. To this day, there are no clues as to the continual evolution of my mother’s name. The ritual of saying grace before an Ellis family meal is worth mentioning. Whenever Grandma Riley was present, it was a very formal and rigid process. Before placing a spoonful of food on their plates, every person at the table would kneel with heads bowed as the food was blessed. At the Riley farm, it was Grandpa Riley who most often said grace. His blessings were short and to the point; only a few well-used words were uttered. On rare occasions, Grandpa would attempt to be creative, but this would result in a series of comments going in all directions and understood by no one. Grandma Riley could anticipate a “non-directed” blessing after the fourth or fifth word. When the red flag went up, she would immediately mutter, “Ole nigger don’t know what he’s saying” — Grandpa’s cue for a quick end to the prayer. No matter what he was saying, his next words would be, “Thank you, Jesus. Amen.” 2. Obtaining knowledge through learning is the key to self-improvement and getting ahead in a very competitive world. Grandma Ellis constantly emphasized the necessity of obtaining a good education. Having a good education is especially important for dealing with crucial issues such as segregation and racism. You obtain knowledge through a lifelong learning process, and the Ellis children were taught that one should never feel that he or she has learned enough. 3. Goals for improving oneself must be established and actions should always contribute to meeting those goals. The time and energy available to meet goals is limited. It is critical that every minute, every ounce of energy, and all resources be utilized efficiently to meet goals. Goals normally have time constraints. For example, before basketball season, next year, during college, before I’m 40, and during my lifetime are common time limitations we face. On behalf of Maggie and Whit Ellis, I suggest that their approach in this important area be called “the concept of minimal lateral energy.” I hope they don’t mind. The only desirable energy is energy that moves us forward towards goals. Less productive energy that promotes standing in place is lateral energy — something that does nothing to help us reach our goals. In modern times the principle of minimum lateral energy is called strategic planning or being focused. Here’s a simple example of Grandma Ellis’ concept. One of the boys returned from school after a serious argument with a schoolmate and asked his mother, “Should I go back to school and fight the boy?” Grandma simply replied, “How is that going to help you get good grades in your classes?” 4. You should use your full potential in every task you face. Winning is not as important as doing your best! A good example of using your full potential is when Francis, then 10 years old, entered an 8-mile running race sponsored by Douglass School. The race began in Fallis, Oklahoma, and ended in downtown Chandler. All the other competitors were 16 years old and above. Several were adults. Francis was smaller than the other runners and practiced hard to prepare for the event. Francis completed the entire eight miles, never stopping to rest or walk. This feat required every ounce of strength in his small body. He came in last, just a few feet behind an older boy running in front of him. Before the race his mother had told him, “Don’t feel bad if you don’t win. All you can do is your best.” No one had even expected Francis to finish the race. The crowd cheered in celebration and amazement as young Francis Ellis crossed the finish line, still running at a slow but steady pace. Francis did not win a prize. However, a collection was taken up from the exuberant crowd, and the money was used to purchase Francis a sweater for his outstanding efforts. People with whom I spoke recalled the race as a “good example of how doing your best may not always win first place, but people will honor your good character and you will be a much better person for the effort.” After the race, Francis returned home exhausted, where he received the most important reward of all — a big hug from Maggie Ellis and smiles from all of his brothers and sisters. Francis’ youthful determination would stay with him all of his life. It was especially useful during WWII. He was one of the army’s few black Infantry Company Commanders and he survived hand-to-hand combat in the South Pacific area. 5. Respect and dignity must be given and received. One must respect others, but at the same time respect from others must be earned. Part of this principle was telling the truth. Telling a lie was disrespectful to one’s self as well as to the victim of a false statement. Segregation, racism, and poverty often made this family principle difficult to follow. Disrespect toward black people was exhibited in all aspects of life, serving as the underlying factor in segregation. Ora Ellis has a vivid memory related to disrespect. About eight years of age, Ora was sent to a local store to buy flour. As he entered the store, a small group of white men were sitting around a pot-bellied stove and talking. They stopped their conversation as he entered the front of the store. Ora went to the counter to make his purchase. The storeowner working behind the counter stopped to accommodate him. After Ora had spoken, the storeowner reached out and began patting his head. He looked at the men sitting at the stove and laughed as he said, “You can always tell what a nigger wants by rubbing his head.” Ora immediately turned around and departed without saying a word. The whole group burst into laughter. The storeowner shouted after him, “What’s the matter boy? Can’t take a little joke?” The laughter of the men faded in the distance as Ora ran back home. Ora immediately reported the incident to Maggie Ellis. Ora questioned whether he had done the right thing; Maggie responded, “You did exactly the right thing.” After this incident, no Ellis family member ever went inside that store again. Respect must be given as well as received! Mutual respect among family members was always maintained. In my lifetime, I have never witnessed my mother or any one of her siblings raise their voices at each other. There was a special way of resolving conflict. A large part of it was being morally correct when entering a conflictive situation. Self-respect and dignity were important characteristics that should never be sacrificed. Modesty, another important value, was connected to giving and commanding respect. One should not boast or brag. If you make good decisions, treat people with respect, and do your best, the people around you will boast and brag on your behalf. 6. Teamwork and sacrifice improve everyone’s chance of meeting individual and group goals. The Ellis family was a strong, cohesive group. They worked together on every task. Teamwork began when each child was given a task important to the operation of the restaurant. It continued at Douglass School, where the older Ellis children would help the younger ones with their homework, and in the children’s mutual support of each other at Langston University. It has lasted throughout the family's lifetime. During the rough years of the Depression, every employed Ellis child gave their earnings to Maggie, who utilized the money according to the needs of the family. Her discretion was never questioned. There were no self-serving agendas and debates about “your money, my money.” The family always came first. The Ellis family core values were a code of conduct guiding the way family members should live. This code was never written, but clearly understood by every member of the family. When the code was broken, corrections were immediately made. Usually Maggie was the disciplinarian. An Ellis child who misbehaved was subject to a spanking. There were no concerns that spanking was cruel and unusual punishment. To this day, my uncles recall that any punishment they received was deserved. They believe this type of childhood discipline made them better adults. Whit Ellis fully supported discipline within the family. His shadowing image was always part of the family disciplinary system. However, when punishment was prescribed, he seldom carried out sentences. After spending up to 14 hours a day in the restaurant, Grandpa Whit would return home with just enough energy to relax and retire for the evening. His supervision of family justice was limited to incidents occurring in the restaurant. The investigation of violations of the family code and any subsequent corrections were normally Maggie’s responsibility. She was a master at this task. Most often, younger children were the violators. By age 13 or 14, an Ellis child was already familiar with adult responsibilities. At this age their task was to set a good example for their younger siblings. Hasko Ellis, the sixth child of Maggie and Whit Ellis, was the most frequent recipient of Maggie’s corporal punishment. Called “Big Dog” by all of the family, Hasko was one of the three Ellis children with red hair. He was the family clown, and, as you will learn in Chapter 5, he was the family’s biggest mischief instigator. One of Hasko’s spankings typifies punishment of an Ellis child who violated the family code. Grandma Ellis would summon the perpetrator to the middle of the kitchen, where she waited with her special spanking tool: a worn-out, thin leather belt from a foot-powered Singer sewing machine. The belt was conspicuously hung on a nail on the kitchen wall — a reminder to all potential wrongdoers. For most of the kids, it was a powerful deterrent. It didn’t always work with Hasko. Grandma Ellis was known for her metronome precision in delivering corporal punishment, while at the same time providing counseling. A typical spanking was short and to the point – a series of loud “whacks” interrupted by Grandma’s counseling and commentary. Whack! “Didn’t you hear what I said?” Whack! “I thought I told you last week not to come home late.” Whack! “You know when you come home late, I sit here worrying about what happened to you.” Whack! I know you are going to do something wrong next week, so I’m giving you something in advance.” Whack! Whack! To break the cadence and gain sympathy, Hasko would often shout, “I’m going to run away from home.” Grandma Ellis would respond, “Well, that’s all right with me; here’s something to take with you.” Whack! Whack! Whack! With his punishment served, the perpetrator was allowed to leave the room. On October 29, 1929, the nationwide Depression in the United States officially began with the fall of the stock market. This day was called “Black Tuesday.” Lincoln County’s Depression began five or six years before the stock market crash and continued well past the time most other parts of the United States had fully recovered. In Oklahoma, the Depression started when cotton began losing its position as the chief cash crop — roughly 1925 — and lasted until the beginning of WWII. Other factors added to the impact of the Depression in Oklahoma and throughout the Midwest, including a boll weevil plague that drastically reduced the size of the cotton crop and a long period of drought affecting all agriculture and livestock farming. This was the infamous era of the Dust Bowl. Chandler’s black community, with its heavy dependence on cotton production, was gravely affected by the failing of cotton crops. As the local cotton crop was reduced, many families lost their only cash income. This required them to spend a large part of the year picking cotton in other areas — some of them quite remote. Migrant farming took some Chandler residents as far away as Arizona. The Ellis family remembers the Depression as one of the toughest periods of their history. It was a full-time struggle simply finding enough to eat. Planning anything beyond mere subsistence was very difficult. Surviving the Depression forced each family member to fully utilize the core values taught by Maggie and Whit Ellis. While the restaurant remained open, business was slow. The dwindling restaurant income fell short of the money needed to sustain the family; every family member had to find a job. All money earned was given to Maggie, who skillfully managed the family’s income, making sure enough was set aside to cover the basic needs. If there was extra money, which seldom was the case, it was spent on clothes, schooling, amusements, and other things The following are a few of the Depression stories most often mentioned by the family. They cover the general period 1925-1935 and demonstrate the core values in action. In 1927, the Ellis family started its own poultry business. While the entire family was involved, Hasko played a leading role. The business was launched with a “how-to-do-it kit” from a mail order firm. The kit provided specific details on how to set up and manage a poultry farm. The Ellis operation began with the hatching of chicks from fertile eggs. Some of the chicks would be raised for sale as meat and some would be used as laying hens. An essential item for the business was an incubator. Since the family had no money to purchase one, the boys built their own – a simple apparatus made by insulating a wooden box with hay and making a stand to hold the box over a lantern. The lantern provided the heat for the incubator, where the temperature had to be maintained between 100 and 103 degrees for a three-week period. The eggs placed in the incubator were selected depending on the ultimate use for the chicks — to provide meat or to lay eggs. An “X” was placed on one side of each egg to ensure they were rotated properly. During the incubation period, the boys worked 24-hour shifts to monitor the temperature inside the incubator. Two large chicken houses were built next to the outhouse to house the chicks as they became larger and to provide a home for the chickens that would produce eggs. The chickens and the eggs were sold door-to-door throughout the streets of Chandler. The poultry business provided food for the family as well as supplemental family income. As the Depression continued, canning food became a major activity. All members of the family, plus relatives, were involved. From their science class at Douglass School, the Ellis children learned the principles of canning food. They were simple. First, the temperature of the food item had to be at a level where bacteria could not survive. Second, the heated food then had to be sealed in an environment where bacteria could not grow. This environment was the canning jar. The processes for these two steps were set up in an assembly line worked by seven or eight family members. Sometimes, the canning would last four or five days and result in 800-900 jars of food. Just about any type of vegetable, fruit, or meat could be canned. In 1932, James Ellis remembers Grandma Ellis set a goal of canning 1,000 jars, but she ran out of food and was forced to stop at 987 jars. At the height of the Depression, even canned food was hard to produce. One day a farmer brought a truckload of turnips to sell in Chandler. At the end of the day he had sold almost nothing, so he offered to give Whit Ellis the entire load of turnips free of charge. The turnips were dumped on the side of the road and left in the charge of Hasko and several of the boys. The problem was how to transport the turnips to the Ellis home several blocks away. Hasko disappeared for about a half an hour and then returned with a mule drawn wagon. It was later discovered that Hasko borrowed the wagon without informing its owner. The wagon was loaded and the turnips moved to the house on 12th Street. A large hole was dug in the backyard and lined with a thick layer of hay to prevent freezing. For the next six months, the family’s daily meals were heavily supplemented by the turnips. To this day several of my uncles refuse to look at turnips! Others consider the turnip a life saver and take great pride in eating them. The Ellis Position at A. D. Wright’s Drugstore Between 1927 and 1940, five of the Ellis boys worked in the same position at A.D. Wright’s drug store. They cleaned the store and did other odds and ends. George, who began his job there at 12 years of age, was the last Ellis child to hold the position. Beginning with James, the cleaning position was handed from one boy to the next. The pay was one dollar per week for about two hours of work per day. The boys remember the weekly chore of cleaning the front windows of the store. This was an interesting task as several of the windows were made with large curves. One big advantage of the drugstore job was having access to unsold magazines and newspapers. The old reading materials were taken home by the boys to become one of several resources for the family’s home library. Sometimes dairy products and food were also given to the boys. A. D. Wright was quite happy at the endless supply of hardworking and honest labor provided by the Ellis family. The salary he paid was not much but steadily contributed to the overall family income.

In mid-1928, job opportunities in Chandler were non-existant. Relatives in California boasted about good employment there. Whit Ellis Jr. decided to leave Chandler and try his luck in California. Within several months, Cliff, James, and Hasko followed. Whit arrived inSan Diego, California, and began work in a brick factory. When the other brothers arrived, they all shared a small apartment not far from the brick factory. Things went well the first month or so; then their luck changed. On October 29, 1929, the stock market crashed. The brick factory closed, and it was impossible to find employment. Whit reorganized his brothers to pursue other employment opportunities. One of them was a shoeshine stand where they all worked. After a few months, the brick factory reopened and James was rehired. Soon afterwards, his right hand was crushed in a terrible accident. He nearly lost his arm to a gangrene infection related to poor medical treatment. He returned to Oklahoma. Whit Jr. became seriously ill. The unknown illness lingered and worsened. He died on October 30, 1930. It was a terrible blow to the entire family. Hasko and several of Ann Riley’s grandchildren living in California accompanied Whit back to Chandler for burial. Cliff remained in California a few more months and then returned to Chandler. He eventually returned to California to raise a family and remained there the rest of his life. One unusual event related to Whit Jr.’s death is worth mentioning. During Whit’s illness, Grandma Ellis was constantly updated on his condition by telegrams sent from California. She knew he was seriously ill, but had not received any new information in more than a week. One day, in the middle of her daily afternoon nap in the small room at the back of the Ellis restaurant, she suddenly awakened, sat up, and in a loud voice said, “He’s dead.” Within a few hours a telegram arrived announcing Whit’s death. As a young teenager, Francis contributed to the family income by working at Smiths’ Dairy. Smith’s was one of two dairies in Chandler. The Smith dairy was a very unsophisticated operation, housed in one room of the Smith home. The cows grazed and were milked in a rented pasture just outside of town. Twice a day, 25-gallon cans of fresh milk were brought to the Smith house on a horse-drawn wagon. Within two hours after the cows provided the milk, the fresh dairy product was in the hands of customers. For doing odd jobs twice a day, Francis received a dollar per week. As additional compensation, Frank was allowed to take home a gallon of milk each day. In 1930, Whit Ellis began having health problems. Within a year, it became difficult for him to walk and stand on his feet for long periods of time. His jovial attitude began to disappear. He became humorless, impatient, and easily irritated. He developed painful open sores on his lower legs. Every day, Maggie would bathe his sores with salt water, but they would not heal properly. Grandpa Whit’s health rapidly deteriorated. Finally he became completely bedridden. The family has never been sure of his exact illness, but his symptoms suggests diabetes. Maggie Ellis and the children began running the restaurant. Grandpa Whit was bedridden for 17 months. Early in this period, he suffered a stroke that caused him to lose his speech temporarily and to permanently lose the ability to leave bed unassisted. On April 16, 1932, the head of the Ellis family died after a long and productive life. He was 62 years of age. His legacy was the co-parenting of 10 unusually talented and accomplished children. Maggie Ellis was devastated by the loss of her husband. Watching him gradually fade away and accepting the great responsibilities he left behind were emotional strains. She was advised by a doctor to relax and refrain from any type of work for several months. She relaxed for a few weeks and then returned to her usual chores, plus the additional ones necessitated by Whit’s death. The Ellis Restaurant remained open for a few additional months, but finally closed with several thousand dollars in uncollected debts. Whit and Maggie Ellis raised their family in accordance with a set of values. The values were guidelines for addressing life’s everyday problems. While not written, family members understood the values and the consequences for violating them. The guidelines were general enough to leave room for new and creative approaches but inclusive enough to motivate everyone to follow them with great care. The values centered around a belief in God, hard work, honesty, respecting others as well as yourself, self-development, and family loyalty. The children of Maggie and Whit Ellis had one important advantage. They were surrounded by role model adults who included their mother and father, their grandparents and the local school principal. All of whom worked together in providing a positive environment for the family. In many other families, such positive role models and a healthy environment were not readily available.

|

||