|

Opening a first-rate restaurant in Oklahoma in the 1890s was a remarkable achievement for a young black man with limited formal education. Between 1890 and 1932, Whit Ellis owned five businesses. He worked 14 hours a day in his enterprises. While it left little time for anything else, it was a great learning place for his children. As described in Chapter 3, the Monrovia Restaurant in Guthrie, Oklahoma, was Whit’s initial business venture. The Monrovia was named after the capital city of Liberia. It was one of the many ports visited by Whit Ellis during his years at sea. There was a profound message in his choice of the restaurant’s name. He was honoring the name of the capital city of a country of free black people governed by black people. Liberia was founded in West Africa in 1816 as a place of resettlement for freed slaves from America. In 1841, its colonists were granted the freedom to govern themselves. In 1847, Liberia became an independent republic. It was granted full recognition by Britain in 1848, France in 1852, and by the United States in 1862. The Monrovia Restaurant was the realization of Grandpa Ellis’ dreams. In his years of working as a ship’s cook, he recognized his aptitude and love for the food service industry. He determined that someday Whit Ellis would be the boss of Whit Ellis. He observed a broad scope of how things are best done. From this grew the Monrovia Restaurant, one of Oklahoma’s first top-quality eating establishments. Grandpa Ellis often shared fond memories of the city of Monrovia. He emphasized that the black people had dignity, freedom, and a pioneering spirit. He talked of returning to Monrovia sometime later in his life, but unfortunately, that trip never happened.

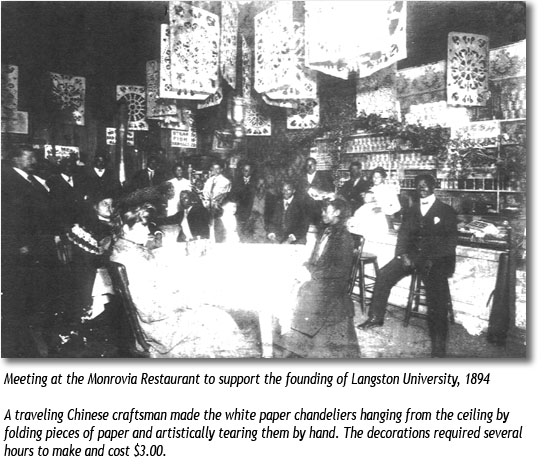

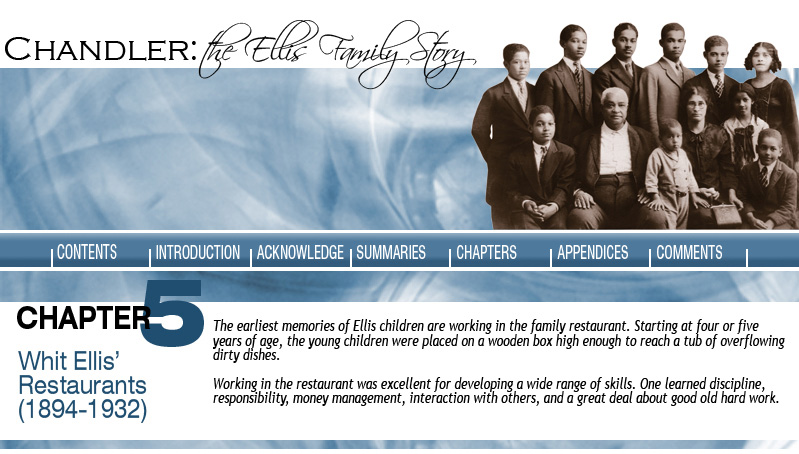

The above photo, taken in 1894 during a special meeting held at the Monrovia Restaurant, is significant in several ways. First, various black businessmen and dignitaries, including Edwin P. McCabe (on the far left), were present. McCabe helped found the town of Langston, Oklahoma, as part of a larger program to establish more than twenty-five “black settlements” in the Oklahoma Indian Territory. McCabe’s ultimate goal was to establish Oklahoma as a “black state.” This never happened. Also important, the photo depicts blacks as businessmen — leaders and decision-makers, as opposed to field hands and servants. For blacks, in Oklahoma in the 1890s, this was a seldom seen positive image. The objective of the meeting at the Monrovia was to organize support for the territories’ first institution of higher learning for “colored” citizens to be located in Langston, Oklahoma. In 1941, this institute, The Colored Agricultural and Normal University, became formally known as Langston University. The majority of Monrovia Restaurant customers were territorial legislative representatives living nearby. In 1897, Whit sold the Monrovia and began working in Stillwater, Oklahoma. In 1899, he met Maggie Ellis. They fell in love and were married in 1900.

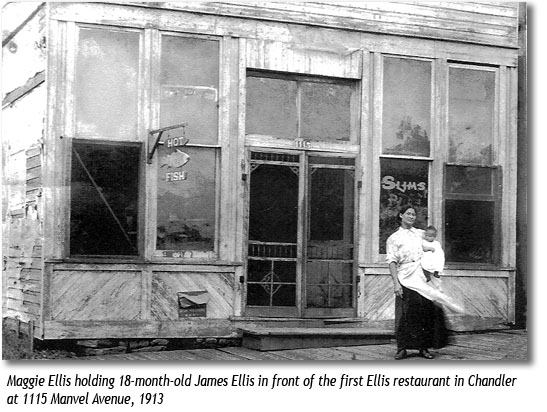

Immediately after his marriage, Whit opened his second restaurant in Stillwater, Oklahoma. This venture was not successful and closed after a short period of time. In 1902, Grandpa Ellis returned to Guthrie, Oklahoma, with Maggie and their first child, Roberta. He reopened the Monrovia Restaurant in its original location. In 1904, while still in Guthrie, Whit and Maggie’s daughter, known only as “Baby Ellis,” was born. She died from choking on a peanut shell after six short months of life. Maggie was devastated by the loss of her second child. She suffered from guilt and often said, “The baby would not have died if I was in Chandler with Momma.” In 1905, Whit Ellis, Jr. was born. In 1906, Whit sold the Monrovia Restaurant a second time and returned to Chandler. He opened a small grocery store and restaurant at 1115 Manvel Avenue.

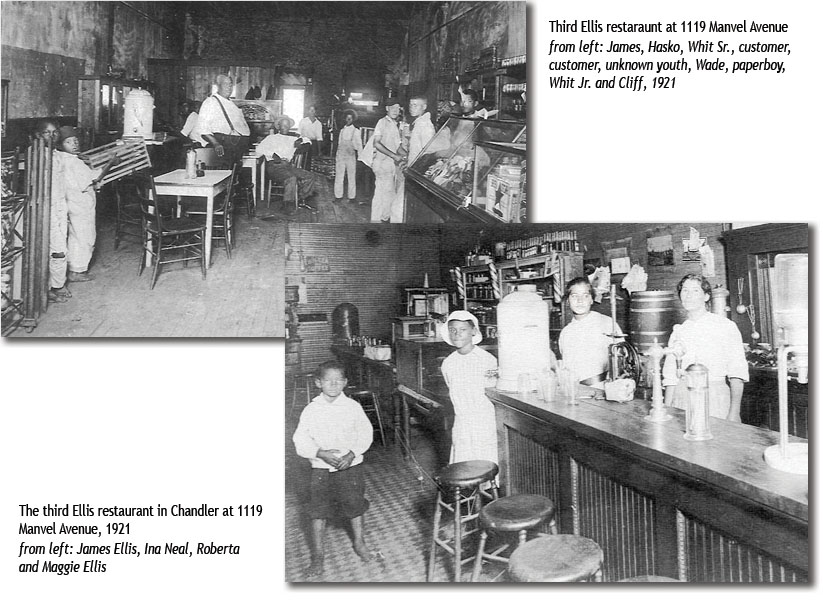

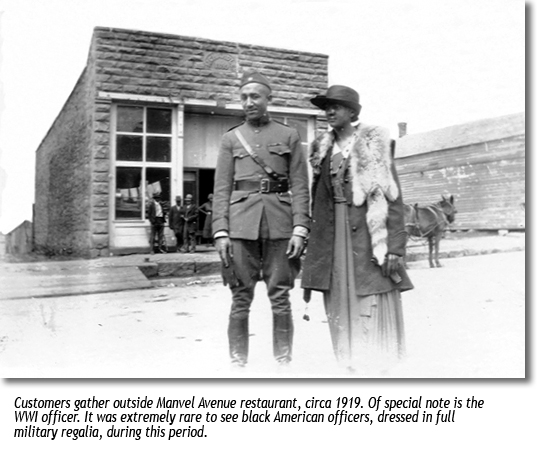

The store was officially known as Whit Ellis’ Store. The building was constructed of flimsy wooden strips and was quite fragile. However, the store was spacious and carried a wide array of groceries and household goods such as flour, sugar, bread, salt, crackers, hardware, pots, pans, and anything else that a family might need. The store also incorporated a small kitchen and restaurant. It is apparent that Grandpa Ellis had a good business head and was not straying too far from the food industry. Whit Ellis’ Store, totally owned and operated by a black entrepreneur, was the first of its kind in Chandler. It quickly became a focal point for both white and black customers. Black citizens who felt uncomfortable buying from white merchants especially welcomed it. The store was filled with the smells of fresh produce, the burlap bags used to store goods, and the heavy scent of tobacco was constantly in the air. Someone always seemed to be smoking. Next to the stove was a spittoon for those who chose “smokeless” tobacco. In the middle of the store, three or four chairs surrounded a large pot-bellied stove. Providing this cozy conversation center was the etiquette of the time. Customers enjoyed a space where they could sit and chat and socialize after making a purchase. Across the street from the restaurant was a large watering trough for horses. On Saturday nights, gentlemen who drank more than their share at the local saloons often occupied it. Drunks, partially submerged in the trough, provided quite a show as they talked or sang to themselves, oblivious to the rest of the world. Whit Ellis never complained about his long workdays; he seemed to enjoy every minute. Regardless of the workload, he made it a point to welcome customers with a warm and personal touch. He was providing goods, foods, and good conversation. As the town grew, so did Whit’s restaurant business. He served customers of all races. Many were Indians who were not allowed in white establishments. His Indian patronage greatly increased at the end of each month when the Bureau of Indian Affairs distributed Federal assistance money to the local tribes. Cliff, Wade and Jim were born in 1907, 1909 and 1911, respectively. The Ellis family wasn’t the only thing that continued to expand. In 1912, Whit moved the store to a much larger, two-story facility, directly across the street. The new store still carried household goods, but this time there was more emphasis on serving food. Whit changed the name accordingly — to Whit Ellis’ Restaurant. In 1919, Whit moved the restaurant a third time to its final location at 1119 Manvel Avenue. This upscale facility is seen in the following photos:

Family members primarily staffed the Ellis restaurants. Grandpa Whit always handled the jobs of selling and collecting money. As the family grew, Maggie Ellis spent less time at the restaurant. However, she was always involved in some aspect of the business. At the 12th Street house, she prepared cakes, pies, and other items sold in the restaurant. The children did a wide variety of chores. Jim and Roberta became excellent short-order cooks. Frank, Ora, Cliff and Wade spent much of their time cleaning fish, washing dishes, shelling peas, shucking corn and making ice cream. Hasko did a little of everything. The third Chandler Ellis Restaurant, at 1119 Manvel Avenue, is the one most remembered by the family. The main dishes served were beef, pork chops, beef stew, and a breakfast menu of bacon, eggs, and grits with biscuits. Grandpa Whit’s chili was the house special. A large pot of it was always simmering on the stove. People would come from miles around to enjoy the chili. Some even brought their own pots and pans to take the house special home to share with family members. Several types of desserts were also available. When this final location opened in 1919, Ann and George were still not born.

In 1925, a barbershop run by Columbus Irvin was established in a small room in the front part of the restaurant, with its own private entrance from Manvel Avenue. The early 1920s were the “heydays” of Whit’s Restaurant business. The following are a few of the most interesting events. The Black Dispatch, founded by Roscoe Dungee and published from 1914 until 1981, was the major source of information about Oklahoma’s black communities and issues. It was distributed by all eight Ellis boys. The family’s participation was recognized in the February 29, 1936, issue of the paper. A group picture of the Ellis boys was featured on the front page. The article mentioned that eight Ellis children had been distributors of the newspaper and were “developing into fine, outstanding leaders among the younger generation of the state.” It should be noted the photo was taken several years earlier, in 1928.

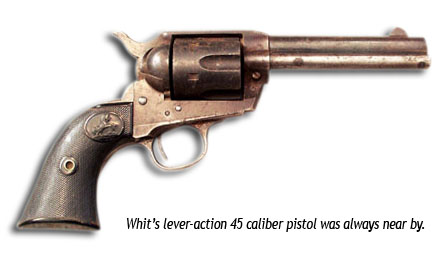

Grandpa Whit owned a six-shot, lever action Colt 45 pistol. Twenty-four hours a day the weapon was either on his person or within arms’ reach. At seven a.m. every morning, Grandpa Whit arose and dressed. After putting on his pants and shoes he would neatly tuck in his white shirt under the large suspenders holding up his pants. His last step was to pick up his pistol from the small stand near the bed where it had been resting since nine p.m. the night before. After eating a quick breakfast and completing a few tasks around the house, he would make the five-minute walk to his restaurant. Immediately after arriving at the restaurant and opening the door, he would go to the cash box and place the pistol in a small slot under the cash box, where it would stay for the remainder of the day unless Grandpa had to leave the restaurant. If an outside trip was made, the pistol would be neatly tucked in his pants with the edge of the handle just barely visible. This made it easy to draw the pistol in case of an emergency, and it made it clear that, if needed, Grandpa was armed and willing to use the pistol.

At about eight p.m., or whenever the final customer departed, Grandpa Whit would lock the restaurant and pack up his pistol. This routine continued until 1930, when he became ill and could no longer work at the restaurant. In general, Whit Ellis was a jovial person who liked people. He often joked with his customers as they visited the restaurant. However, when provoked, he could show a different side of his personality and become violent. We noted the incident that took place in Alabama when Whit was only 14 years old. That event resulted in the deaths of two men and forced Whit to become a fugitive from the law. In 1927, he was provoked into a violent confrontation in the restaurant on Manvel Avenue. Grandpa Whit was experiencing financial problems. Customers were not paying long overdue bills. He was worried about losing the restaurant and concerned about not being able to support the family. On payday Friday, a customer with a seriously overdue bill entered the restaurant to purchase goods. Whit had just been discussing the long list of outstanding debts with Maggie. The customer had a large amount of money and obviously was drinking before his arrival at the restaurant. After he paid cash for several items and started to leave the store without mentioning his overdue bills, Whit stopped him and asked, “When are you going to pay some of the money you owe me?” The man looked at him and profanely responded, “Whit, I ain’t gonna pay you a d*#% thing!” Grandpa Whit had anticipated the disrespectful response. He launched his huge, 300-pound body at the customer and hit him in the jaw with one massive punch. The customer sailed through the air for about four feet and landed at the base of a metal frame used to dispense paper for wrapping groceries. His head struck with such force that it broke the metal base in several pieces. The man lay on the floor, unconscious and bleeding profusely from a large head wound. Everyone in the restaurant thought he was dead. Fortunately, he continued breathing and regained consciousness after several minutes. Members of his family came and carried him out of the restaurant. The man never returned to the restaurant; his bill remains uncollected. Whit and the other family members never discussed the incident.

The town busybody, Mrs. Lovely, was an older widow who hated the world. She was notorious for her dislike of children, regardless of their color. Mrs. Lovely constantly scolded the Ellis boys because their shortcut home from school crossed the corner of her property. At the close of school she would often wait at the shortcut, brandishing a large stick and threatening to strike anyone who dared place a foot on her property. Daily, at 5:00 p.m., Mrs. Lovely would visit her brother who lived near the Ellis Restaurant. She used the alley running behind the Ellis restaurant as her shortcut. This was an invasion of the Ellis boys’ territory because every day they played baseball with friends in the lot behind the restaurant. Mrs. Lovely would take the shortcut, passing within 15 feet of the boys playing ball. With every near encounter, she would double the speed of her walk and look straight ahead, refusing to acknowledge the boys’ presence. For a little mischief, the boys stopped their game and stared at her until she passed out of sight. It was a staring match without eyes ever meeting. No one lost and no one won. One day Hasko Ellis decided to act on the tension between Mrs. Lovely and the children. Hasko, or “Big Dog,” as all of the family called him, was one of three children with red hair. He was the undisputed family clown. If there was humor in a situation, he would find it. He was creative and clever enough to plan his mischievous activities in such a way that blame would always fall on others. His younger brother, Ora, was the most frequent victim of his schemes. For this special plan, Hasko recruited his brothers and the group that played baseball behind the restaurant. Knowing that Mrs. Lovely was extremely curious — in more direct words, nosey — Hasko developed a scheme specially suited for her. Each member of the baseball group promised to participate by contributing a small “gift” to be left in the middle of the alley at the exact time of Mrs. Lovely’s daily trip. The contributions would take nothing more than a short trip to the outhouse at the opportune moment. The next day at 4:30 p.m., contributions were collected and consolidated. The smell of the combined efforts left no doubt as to the nature of the special gift. The gift was placed in a small box and neatly wrapped to appear as something important, accidentally dropped in the alley. At precisely 4:50 p.m. the gift was placed in the middle of the alley. The baseball group then hid behind a large clump of bushes off to one side and between the restaurant and the alley. As usual, Mrs. Lovely appeared at exactly 5:00 p.m. There was complete silence in the alley; even the birds appeared to stop chirping! Mrs. Lovely took several quick glances, probably wondering what had happened to the daily baseball game. She then continued her journey. All of the baseball team was staring from their hidden position behind the bushes. Several of them began to snicker. They could hardly contain their laughter. Mrs. Lovely quickly passed the “present,” then came to a halt several feet from it. She glanced to either side to see if anyone was looking. She then took several backwards steps, stopping directly above the gift. She picked up the parcel and shook it. It took only a split second to recognize the special fragrance of the gift. Mrs. Lovely realized she was the victim of a prank and began shouting obscenities toward the area where the boys usually played. She angrily threw the unwanted gift to the ground and stormed off down the alley. The hiding group burst into laughter that could be heard around the entire block. After the incident, to avoid meeting Mrs. Lovely, the players agreed to temporarily change the location of the baseball game. Mrs. Lovely also chose another shortcut for her daily visit.

THE SECRET ATTEMPT TO REMOVE WHIT ELLIS’ RESTAURANT FROM MAIN STREET In the mid-1920s, Whit Ellis’ Restaurant was at its peak. Sales were growing; the restaurant was well known and considered one of the city’s best businesses. Whit was well known and respected by the citizens of Chandler. It was at this time that a group of white merchants carried out a scheme to permanently remove Whit Ellis from the main street of Chandler. The white owner of a nearby car dealership began making daily visits to Whit’s Restaurant. The car dealer would spend an hour talking about the weather, business, the development of Chandler, and many other topics. The visits appeared to be a friendly gesture and were welcomed by both Maggie and Whit. After several months, the car dealer began asking questions about Whit selling his business at a significant profit. Discussion about selling the restaurant gradually became the main focus of the visits. Finally, Whit agreed to sell, with the intention of opening a larger business somewhere else on Manvel Avenue. The papers were prepared and the day of the sale came. Whit and Maggie were extremely pleased at being able to make such a large profit. The car dealer, a lawyer, and several other people arrived at Whit’s Restaurant to finalize the sale. The final papers were ready for signature. Whit was taking a last quick look at the sales document when he suddenly stopped in surprise. Buried on the last page of the document was a condition not previously mentioned. After sale of the restaurant, Whit would not be able to open another business on the Main Street of Chandler! Whit suddenly realized what the “friendly” chats really meant. It had been a scheme by a group of white businesses to get black businesses off the main street of Chandler. Whit slowly read aloud the paragraph with the new condition. After finishing, he paused for a moment and then stood up and said in a cool and composed voice, “I am no longer interested in selling the business and would appreciate you leaving my store. Thank you very much.” He then picked up the papers and rudely threw them in front of the small group of white businessmen who had gathered to witness the sale. Whit quickly escorted the group to the front door. Obviously upset, he returned to his special seat near the cash register. It was several hours before he fully recovered and was able to return to his job as storeowner and manager. All of the Ellis children in the store understood what had happened. After that day, he and Maggie never mentioned the matter again. However, the lesson learned was clear and quickly understood by everyone present. That evening, in very hushed tones the children who had been present at the event shared the incident with other members of the family. Maggie Ellis always performed one important function at the restaurant. She kept records of all business transactions. Grandpa Whit could read and write, but bookkeeping was one of his weaker points. As mentioned in an earlier chapter, Grandma Ellis had completed the 10th grade. At the time, this was a high level of education for any Oklahoman, black or white. She had a good understanding of reading, writing, and arithmetic and could have taught at the primary school level. In late 1928, Maggie warned Whit, “The restaurant is spending more than it is taking in,” and that something needed to be done about it. Maggie noted many customers had not made payments on long overdue accounts. When questioned about their overdue bills, many replied, “Times are tough,” or “Got to pay the white man off first.” She also brought to Whit’s attention that the largest debts were those owed by local ministers. Whit failed to heed Grandma Ellis’ warning about the failing financial status of the restaurant. The Great Depression diminished customers’ ability to buy goods and services and assured that creditors had no money for paying their debts. The restaurant closed in 1932 after Whit’s death. Even when the town recovered from the Depression and people had money, none of the old debts were repaid to Whit Ellis’s widow. Every Ellis child worked in one or more of their father’s restaurants. The restaurants were instrumental in teaching teamwork, work ethics, social skills, a drive to succeed, and many other things. The experiences at the restaurant were an early preview of the challenges the Ellis children would face as they became adults.

|

|