|

Over the years, an Ellis tradition was established; one pioneer family member would leave the Chandler nest to improve his or her life and family. Then the pioneer would form a base supporting the arrival of other family members, who would soon follow. As each member arrived, they would become part of a chain linking the family together through both good and bad times.

This first pioneer adventure began in 1920, the year Roberta entered Langston University. Between that year and 1943, she was followed by all nine of her brothers and sisters who either attended or worked at Langston. In some form or fashion, Roberta helped her siblings complete their education at Langston. Sometimes assistance was financial; sometimes it was moral support encouraging them to do their best and not give up when times were tough. Roberta helped find employment for her siblings, and whenever possible, provided employment herself. Remember, for several years, Roberta was supervisor of the school’s dining hall which was staffed by students. The next Ellis pioneer came several years later in 1929. Whit Jr. ventured to California to escape the nationwide Depression and find employment. Soon after his arrival, Cliff, James, and Ora followed. Hasko was summoned and arrived a few months after the others. Whit was the quick-witted, dashing, and charming eldest son. His red hair and freckles made him very popular with the ladies. Quick to identify business opportunities, Whit provided leadership for the small California group. He helped find housing and employment in addition to acting as the contact point for the family that remained in Chandler. In both of the above adventures, the family worked as a team, always supporting each other. There are several observations worth mentioning. I am personally familiar with all of my aunts and uncles, with the exception of Whit Jr. He died in 1931, nine years before my birth. I cannot recall one instance of my aunts and uncles raising their voices at one another. Disagreements were always worked out with the least amount of conflict. The oldest brother or sister present usually took the leadership role in solving problems. When one family member was having difficulties, the others would always help without being asked. It was a special sense allowing them to know when help was needed by other family members. In 1945, my parents separated while my father was still in the Navy and stationed in Fresno, California. After the separation, my mother, brother Whit, and I arrived in Ann Arbor with nothing but the “clothes on our backs.” My uncles already living there frequently visited our home. At the end of each visit there was always a warm hug and a handshake for my mother. As hands separated, I would often see the edge of a five or ten dollar bill, left in my mother’s hand by one of her thoughtful siblings. During these moments no one spoke; it was not necessary. Everyone understood the right thing to do and did it.

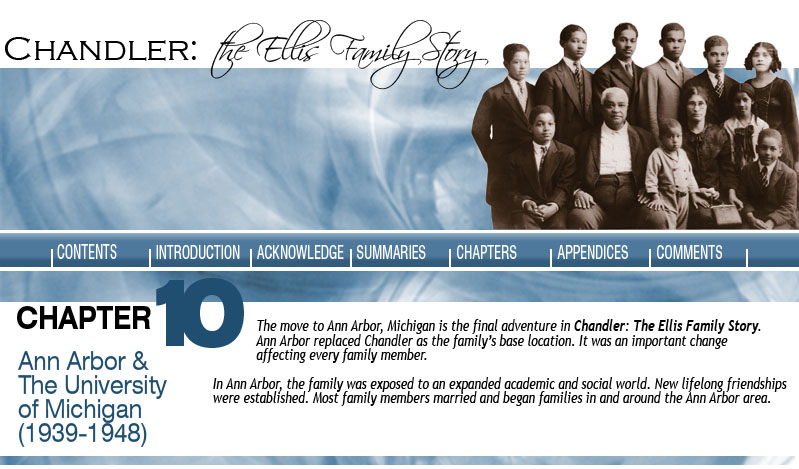

THE MOVE TO MICHIGAN — WADE ELLIS, THE "PIONEER" Wade Ellis was the leader of the move to Michigan. Beginning in 1939, Wade, followed by six of his brothers and sisters, moved to Michigan to attend the University of Michigan. Wade Ellis became an internationally known mathematician and educator. He graduated from Wilberforce University at the age of 18 and began his teaching career in a one-room schoolhouse in rural Oklahoma. He then taught for nine years at the Boys Industrial School in Boley, Oklahoma. In 1938 he received a Master’s Degree in mathematics from the University of New Mexico Graduate School. At the graduation ceremony, because of his color, Wade was required to march at the end of the graduation line.

Wade taught at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee for two years and received a Rosenwald Fellowship to continue his mathematical studies. In 1939, he entered the University of Michigan and in 1944 earned a Ph.D. in mathematics. In the same year, his dissertation was designated the best in his department. While at the U of M, he helped many of his brothers and sisters complete their education at the university. From 1944-1948 Wade worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory as a Section Director. He worked on radar antenna design and developed the idea of looking at the moon’s reflected light flash to determine if the Soviets had detonated an atomic bomb. His research from that project is still classified. In 1948, Wade became an assistant professor at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, where he remained for 19 years. In 1953, he attained the rank of full professor. While in Oberlin, he was a member of the Oberlin City Council and for one term the town’s Vice-Mayor. In 1953-54, Wade took a sabbatical year touring the world. During his voyages he made contacts with many mathematicians from India. In 1959, as Director of the Foreign Visitor program for the Mathematics Summer Workshop Program of the National Science Foundation, he invited mathematicians from around the world to speak at the Foundation’s workshops. From 1967-77, Professor Ellis was an Associate Dean of the Horace B. Rackham School of Graduate Studies at the University of Michigan. After retiring from the University of Michigan, he served as President of Mary Grove College in Detroit, Michigan from 1979-1980. From 1981-87, Professor Ellis was an educational consultant and lecturer in Mexico, Peru, Greece, and Japan. He received the highest civilian award from the Peruvian Government for his work in that country. Wade was an extremely brilliant person. He was always smartly dressed and often wore a bow tie. Wade’s ability to find the bottom line of an issue, organize his thoughts to come to a logical conclusion, and then skillfully defend his position was legendary. This attribute, accompanied by a photographic memory for both the written and spoken word, always made me hesitant to express my thoughts in his presence. I often seemed to lack all the facts — a point he would quickly bring to my attention in a polite but convincing manner. There were several reasons for Wade selecting the University of Michigan to continue his education. His field of study was mathematics and there were only a few schools in the United States with extensive programs in mathematics that would accept black students, among them, the U of M was one of the most well known. Even with a long list of segregation policies, compared to other schools, the U of M treated black students well. In a February, 28, 1989, Detroit Free Press article, Wade Ellis and several other black U of M alumni from the 1930s and 1940s were interviewed for an article celebrating Black History Month. One of the interviewees stated, “The University developed a reputation for seeing to it that blacks were successful.” At the time that type of attitude was not common. The above comment should not be interpreted as the U of M being without prejudicial policies. As in Chandler, racism and segregation were present, but not as well defined as in most other places. A good example is cited in the article mentioned above; Wade commented: “By the time I became a candidate for a doctoral degree, every other mathematics candidate I knew had a job as a teaching fellow. But I had a job in the correspondence study division where I had no contact with any of my students.” In the article Wade explained that his hourly salary in the correspondence study division was only 20% of that received by white teaching assistants. It should be noted that while working on his Ph.D. in mathematics, Wade maintained a straight “A” grade point average, and as mentioned earlier, in 1944 his dissertation was selected as the best in the Math Department of the U of M Graduate School. Wade was one of a handful of black students arriving at the U of M for the fall session in 1939. On Wall Street in Ann Arbor, he found an apartment for his wife and newborn son, William Whit Ellis. The following year Wade invited his brother Francis to attend the U of M summer school and stay in the apartment’s extra bedroom. The original idea was for Francis, who became known as Frank, to spend the summer at the U of M, then return to his regular job as a teacher in Wynnewood, Oklahoma. Frank’s professor at the U of M was so impressed with his work in the summer program that he offered Frank a position as a research assistant. The job included tuition and fees, plus a small stipend for expenses. Frank accepted the job and became the second Ellis family member permanently resettling in Ann Arbor. Wade and Frank decided to combine their limited resources to buy a house, but there were two problems — finding a suitable house that could be purchased by a black buyer and arranging financing to purchase the house. They found a house at 921 Woodlawn Street, only a few blocks from the famous U of M football stadium. It cost $4,000 and required a $400 down payment. Monthly payments would then be $40 per month. Wade had a total of $100 in cash and Frank had nothing. The challenge was where to obtain the additional $300 for the down payment. This problem was solved by one of Ann Arbor’s most colorful “smile makers,” John “Papa John” Easley, a local barber. I will explain the details in subsequent paragraphs. Jim Ellis arrived in Ann Arbor from Oklahoma in 1940 to attend summer school at the U of M. After hearing a description of the harsh Michigan winters, he decided to spend the remainder of his life in a warmer part of the United States. He returned to Oklahoma after the summer session. In late 1941, George Ellis became the third Ellis to arrive and remain in Ann Arbor. Ora, who became known as Herb Ellis, arrived the following year. Ann, my brother and I, and Aunt Roberta, arrived in 1944. All came to rejoin the family at the new “base” and to study at the U of M. By 1946, only Hasko, Jim, and Cliff were not permanently relocated in Ann Arbor. Grandma Riley and Grandma Ellis were also still living in Chandler. During the early 1940s, three of the Ellis boys served in WWII. Hasko, Frank, and George all served overseas from 1943-1946. Frank, a captain, was wounded in the South Pacific. George mentions that during his three years of military service, he only encountered three black officers who were captains. One of them was his brother Frank. George received four campaign medals for his service in Europe.

In the late 1930s, Ann Arbor had a population of about 20,000 people. Then, as now, the U of M was the biggest “business” in town. Our best guess is that the town included several hundred black citizens. In addition, there was a small group of black and Mexican migrant laborers constantly passing through Ann Arbor to work on the railroad. Many of the black citizens came from Canada. They landed there as a result of the Underground Railroad. The Railroad was a system organized during the Civil War to assist escaped slaves. Some of Ann Arbor’s oldest black families include the Cromwells (five generations in Ann Arbor), Spanns, Bakers, Jewetts, Coopers, and others.

There were small groups of blacks located in many parts of the city, but the largest enclave was in the South 4th Avenue area, extending from Ann Street to where 4th Avenue ends at Depot Street, not far from the Ann Arbor Train Station. While blacks lived a rather comfortable life in Ann Arbor, they did not have access to housing in all parts of town. They were not allowed to dine in most local restaurants, except those located on Ann Street. We’ll talk more about Ann Street in just a moment. On campus, with a few rare exceptions, blacks were not permitted to stay in U of M dormitories. Exceptions were made for the few students who had political pull.

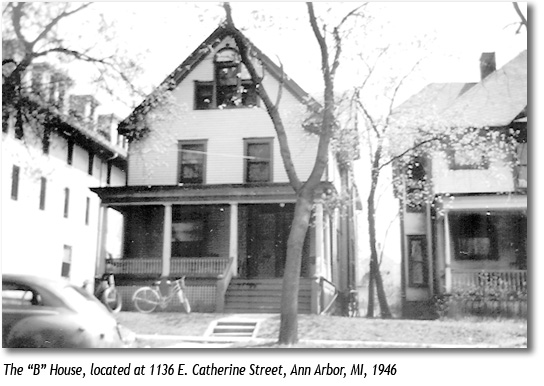

Most black students were housed in private homes recognized by the university. In the early 1940s, there were several locations, the “B” House being one of the best known. It was the central location for black female students and accommodated about 20 persons. We are aware of two “B” houses. A Mrs. Benjamin managed the first one in the late 1930s and early 1940s. It is from Mrs. Benjamin that the name “B” house was derived. The original “B” house was located on the corner of Glen and Ann Streets, one block from the U of M hospital. The second “B” House was closer to the hospital, at 1136 E. Catherine Street. It was run by none other than my aunt, Roberta Ellis Britt. Naturally, every male student knew the “B” house. Now, more than 60 years later, they can instantly recall the address — 1136 East Catherine Street!

Roberta married Claudius G. Britt in Oklahoma. In 1944, she and her new husband moved to Ann Arbor where they soon separated. From 1947-1952, my mother, brother, and I lived with Aunt Roberta at the “B” house on Catherine Street. Roberta was the house mother. Roberta never had her own children but was a “born” teacher and mother — perfect for the “B” house job. She loved to work with young people and was known for her ceaseless patience. She spent tireless hours helping her young ladies adjust to the rigorous study routine at the U of M and to the new social roles they were being required to play as young women.

From her years as mother of the “B” house, she developed many lifelong friendships. Years after graduation students would return to Ann Arbor to pay their respects to Roberta. Prior to the end of WWII, only a few blacks were seen on the U of M campus. The ones who were there, like Wade Ellis, were so burdened with working to pay educational expenses, obtain food, and keep up with their studies, had little time to become friendly with the small community of blacks permanently living in Ann Arbor. However, there were two places where both groups met on a regular basis, on Ann Street and at the Dunbar Center.

In the 1940s, Ann Street was the area where all black businesses were located. The area was one short block in length and only contained 10 establishments. The facilities were all on the North side of Ann Street, between 4th Ave. and Main Street, in the downtown business section. This location was across the street from the county courthouse. This black section of Ann Street included taverns, a pool hall, several restaurants, two barbershops, and a harness shop. Ann Street provided a convenient meeting place and hangout for anyone desiring to be around a lot of black folks. Some male students were regular visitors. If one were a black male and needed a haircut, Ann Street was the only place to go. The black female students avoided Ann Street. Very often, tavern patrons and others would gather outside the saloons and make comments at those passing by. This made the female students uncomfortable — a problem they solved by avoiding that section of town. One white business was still on this part of Ann Street when my mother, brother, and I arrived in 1944. It was an old-fashioned leather shop where goods such as saddles, leather wearing apparel, and whips were sold. The white shop owner had been in the same location since the “good ole days” of the horse and buggy, refusing to relocate when black businesses arrived. His storefront still had the large windows that you see on the front of saloons in western movies. I used to walk into the store to look at the whips neatly hung on the wall, the saddles ready to be thrown over a wild bronco, and the many other things that fascinate kids who have seen too many movies starring Hopalong Cassidy and Bob Steele (two of the biggest cowboy heroes of the time). The heavy smell of fresh leather was always present in the shop. Once a young boy entered the leather shop with all its cowboy items, it was impossible for his imagination to stand still.

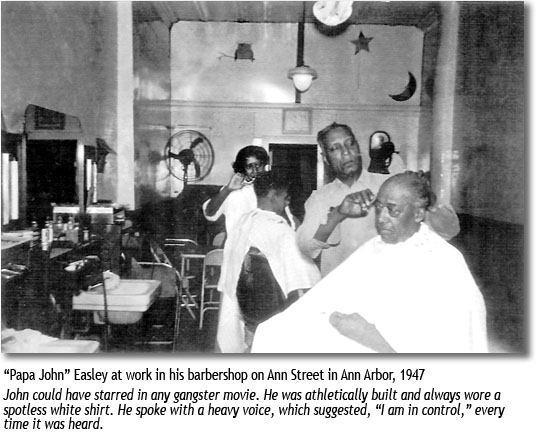

John Easley, a “smile maker,” was the owner of one of Ann Arbor’s two black barbershops and one of the town’s most colorful smile maker. His shop was located in the black section of Ann Street, in the middle of the block, between the pool hall and a tavern — just two doors from the town’s only other black barbershop.

John Easley was nicknamed “Papa John.” Every black citizen in Ann Arbor knew him. My earliest memories of Papa John were the monthly haircuts I received at his famous shop. John could have starred in any movie about black gangsters. He was athletically built and always wore a spotless white shirt. He spoke with a heavy voice, which suggested, “I am in control,” every time it was heard. When you entered the shop, there were always one or two people awaiting their turn for a haircut and several others who were talking or just staring out of the large glass windows at the front of the shop. John never spent more than 15 minutes on any one customer. In the case of small children like myself, he needed no instructions. He would automatically cut hair very short on top and almost bald on the sides.

There were rumors that John was involved in all kinds of illegal activities operated from his barbershop. John eventually served time in the state prison. He always seemed to have a wad of bills neatly rolled up in his pocket.

Earlier we briefly addressed Wade and Frank’s desire to purchase a house at 921 Woodlawn Street. When Wade and Francis faced the problem of obtaining the balance of the down payment on the house, they went to “Papa John” for help. Also originally from Oklahoma, John Easley was Wade and Frank’s barber. John knew the two struggling university students well. One day in 1941, they went to him as a last resort. They needed $300 to complete the $400 down payment to purchase the Woodlawn Street house. Wade and Frank reluctantly entered the shop, not knowing what to expect. They went directly to John as he was trimming the hair of a customer. They quickly related the story of the house they wished to buy and the $300 they lacked. Without hesitating, John reached into his pocket and extracted that amount from the large roll of bills he always kept. As the boys stood in shock, his only comment was, “Pay it back as soon as you can.” They immediately returned to the real estate office to close the deal on the Woodlawn house. I estimate that $300 in the early 1940s had the buying power of about $20, 000 in the year 2007. It was a great deal of money! A few final comments about John Easley: While Papa John may have had problems with the law, he was a perfect gentleman towards our family. When Frank and Wade entered the barbershop for a haircut, they were always the next customers, even if there was a long line ahead of them. John’s excuse for moving them to the front of the line was always, “Sorry, they have an appointment.” When I was very young, my mother accompanied my brother Whit and me to John’s barbershop. Abusive language may have been the norm in the shop, but it was NEVER used when my mother or other ladies were present. John had no flexibility on this issue. He quickly corrected anyone talking loudly or cursing. “What’s the matter with you; don’t you see this lady sitting here? If you can’t talk right, go somewhere else.” There was no further discussion.

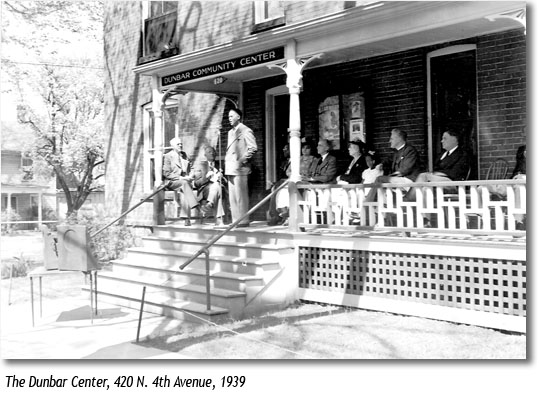

In 1940, two years before her marriage to Herb Ellis, Virginia Wilson began working as Program Director at the Dunbar Center in Ann Arbor, where she worked until 1969. Virginia’s employment at the Center was the beginning of one of the family’s most valued Ann Arbor friendships and an association with one of the legendary persons in the history of Ann Arbor, Doug Williams.

What most people don’t know is that the Dunbar Center was established in 1926 as a housing facility for transit workers employed by the local railroad. It originally was a house with several bedrooms, a living room, and a kitchen reserved to serve blacks and other minorities who could not find accommodations at local hotels. It gradually developed into a center for black community activities. In 1937, a new building to house the center was purchased at 420 N. 4th Avenue. The new center contained a library and meeting rooms and hosted a wide range of activities. The facility and the location were ideal — a large two-story brick building with a basement and attic, located in the middle of the largest black community in Ann Arbor. In 1939, Douglas E. H. Williams was hired as the full-time director of the Dunbar Center, a position he held until his death in 1960. He was a dynamic person who became one the most influential black men in Ann Arbor and a dear friend to every member of the Ellis family.

Under Doug’s leadership, the Dunbar Center continued to be one of the black community’s focal points. It was one of few places where black students and the black community had the opportunity to meet. One big reason for greater student involvement was a special work/study program managed through the Center. The program provided funds to hire youth for various types of work, which gave them the opportunity to earn spending money — something all black students needed. Frank Ellis, Julius Franks, and many other students were hired through this program.

THE HOUSE AT 105 E. SUMMIT STREET In 1943, a second house purchase would play a pivotal role in resettlement of the Ellis family in Ann Arbor. Virginia Wilson and her aunt, Mrs. Sylvia Bynum, bought the house located at 105 E. Summit Street, near the corner of Main and Summit Streets. Virginia Wilson and Herb Ellis would marry in 1943 and reside in the Summit Street house. By the way, Virginia’s sister Blanche, may now be the only remaining child of an American slave in the United States. Beginning in 1943 the Summit Street house became a reception center, providing temporary housing for every Ellis resettling in Ann Arbor and for many others as well. Herb and Frank remodeled the attic of the two-story house as sleeping quarters. For the next 10 years, the house with its sole second-floor bathroom became a temporary home for as many as 20 people at a time. Bathroom time was strictly programmed on a chart posted outside the bathroom. In the morning, each person had a 10-minute time period in the bathroom. All non-urgent needs had to be taken care of outside the “rush hours.” In 1944, after my parents separated in California, my mother, brother, and I moved to Ann Arbor. Our first stop was at the Summit Street house where we were welcomed by an overflowing group of relatives and friends already living there.

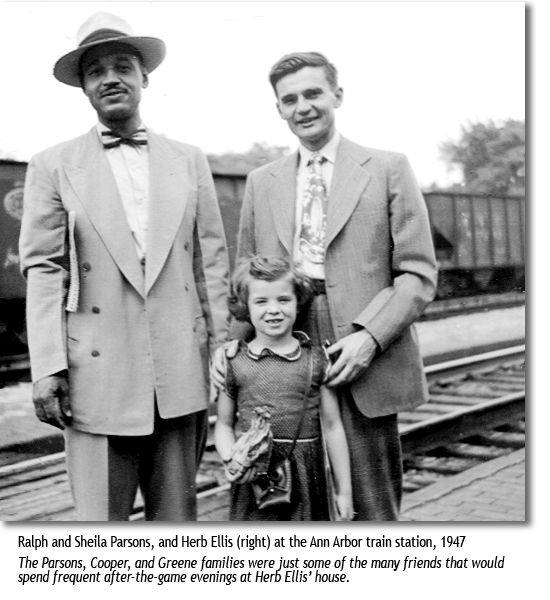

A period of banner years for the Ellis Family was 1945-1948. It was during this period that six of the ten children of Maggie and Whit Ellis permanently resettled in Ann Arbor. In 1946, Frank, Hasko, and George were discharged from the Army after three years of active duty. Hasko returned to Oklahoma, but George and Frank returned to Ann Arbor to complete their educations. In 1946, Frank was temporarily employed by the U of M to assist veterans entering the university under the GI Bill. One of the persons assisting him was Ralph Parsons. Ralph and his wife Jo Anne, along with Ralph’s brother Gardner and his wife Ann, began a very special friendship with the entire Ellis family. More than 50 years later, this friendship is as strong as ever. Frank married Margot Chesnutt in 1946.

In 1947, a group of WWII buddies, friends from the U of M, and others began visits to Ann Arbor to attend home football games. The group included Connie and Bob Baker, Johnny Hearst; the Parsons, Cooper and Walter Greene families, among other close friends. The group would attend the game and then spend the evening eating and drinking and enjoying each other’s company at one of the Ellis homes. This tradition continued for some 20 years. The original group often met at Herb and Virginia's home located at 104 E. Summit Street.

In 1947, my mother returned to Langston University to complete her undergraduate studies. After her graduation the following year, we moved back, completing the Ellis family’s permanent migration to Ann Arbor. The time period covered in Chandler: The Ellis Family Story ends in 1948. By this time, the majority of the children of Maggie and Whit Ellis had moved to the Ann Arbor, Michigan area. They first came to take advantage of the excellent education offered at the U of M and to be with other family members. Six of the seven Ellis children who had studied at the University decided to make their new homes in the Ann Arbor area.

Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan provided an environment where the Ellis children were able to use the lessons learned while living in Oklahoma. Each one of them made maximum use of this opportunity. They established families and became outstanding citizens of their new community. James, Cliff, and Hasko did not resettle in Michigan. James was the only child who continued living in Oklahoma. Cliff found a new life in California, as did Hasko in Texas. All three achieved successes as did their brothers and sisters in Michigan.

|

|||