BACKGROUND

Before state ratification in 1907, many black students attended Oklahoman schools with both white and Indian students. For example, in the early 1890s, Maggie Riley attended integrated schools for grades one through eight in the city of Chandler. As more settlers arrived in Oklahoma, the number of black students requiring an education increased. There was concern about addressing this need, but without further integration of the white school system. In 1904, the territory set aside $4,000 to establish a single facility to serve all of the Oklahoma Territory’s black children desiring an education in the ninth grade and above. This was the Colored Agricultural and Normal University (CA&NU) which, since 1941, has been called “Langston.” The initial funding was allocated to establish grades nine to twelve, along with a four-year college. Academic emphasis was on two-year programs in education, home economics, and agriculture. The small $4,000 budget was expected to cover all expenses!

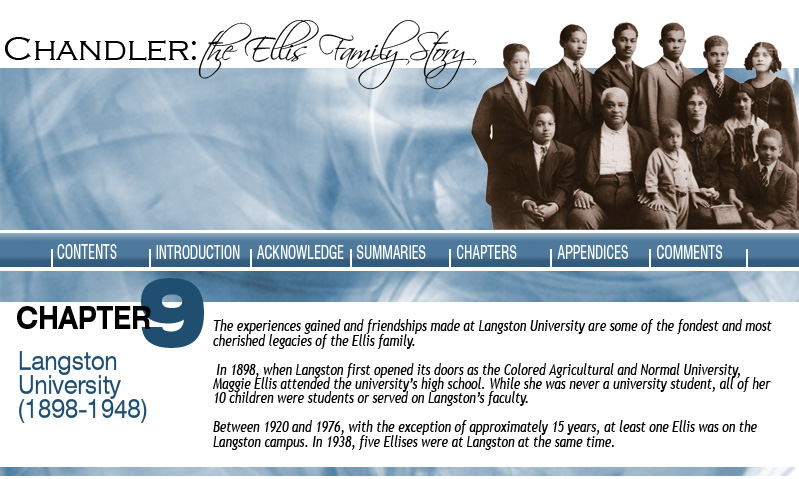

It should be noted that the initial money establishing Langston was primarily provided to support segregation. The education of Oklahoma’s black youth was a distant second objective. In 1898, the first year Langston was open for classes, Maggie Riley attended as a ninth grade student, with the goal of becoming a teacher. We believe Maggie may have also completed the 10th grade.

In 1900, Maggie married and was unable to continue at Langston. However, for the rest of her life, she maintained an unshakable belief that knowledge through learning was the key for gaining equality of the races and escaping poverty.

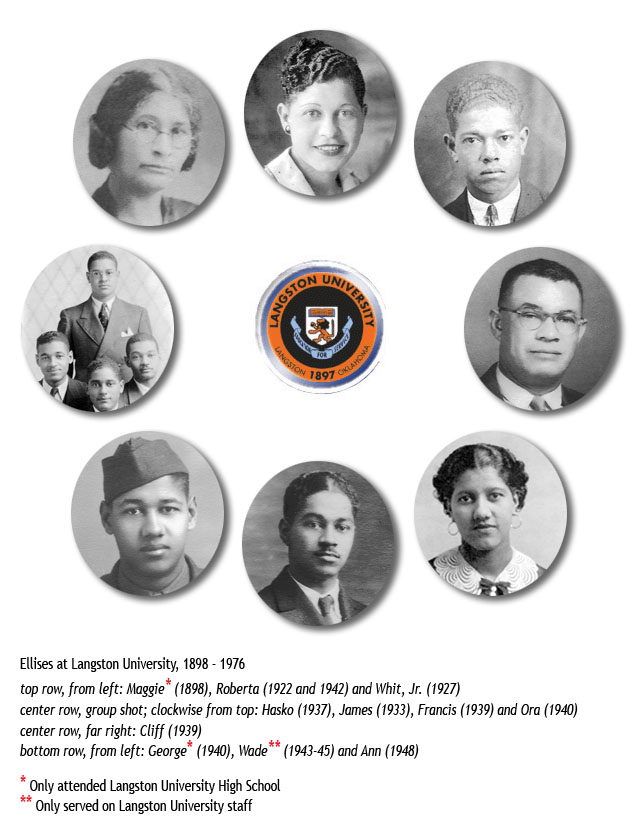

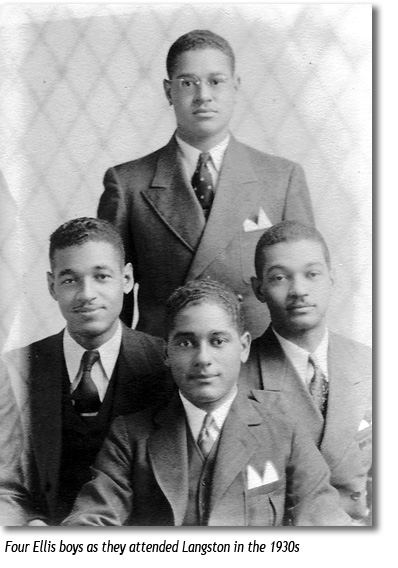

Following their mother’s lead, beginning in 1920, each of Maggie’s ten children either attended or taught (sometimes both) at Langston University. From 1920 until 1976, with the exception of about 15 years, there was at least one Ellis family member on the Langston campus at all times. In one year, 1938, there were five Ellises at Langston: Roberta, Ann, Francis, Hasko, and Cliff.

Several Ellises served on the Langston staff. Roberta graduated first, in 1922. She obtained her second degree in 1942. Between 1930 and 1942 she served Langston University’s staff in various capacities. In 1937, she was a dorm mother for the Phyllis Wheatley girls’ dormitory. From 1938 to1942, she worked as manager of Langston’s dining hall. In this position, she was in charge of all of the work/study program students working in the dining hall. Wade Ellis was listed as a staff member in the math department from 1943 to 1945. From 1948-49, Hasko served as Director of Vocational Agriculture. Jim was the last Ellis at Langston. From 1965 until his retirement in 1976, he served as a Professor in the Math Department.

Ellis family memories of Langston are repeated at every family gathering. The following are a few of the most special ones covering the period 1920 until 1948.

THE LONG, LONG ROAD TO LANGSTON — A 34-MILE WALK!

In the 1920s and 1930s, it was not uncommon for Whit, James, and Cliff to walk to and from Langston. Walking at full speed, the 34-mile, one-way trip would take almost nine hours. The journey was fairly simple: follow the abandoned Rock Island Railroad track, just north of the school. It would take you directly to Chandler. Along the way, one could stop at any farmhouse owned by blacks or whites for rest and water. The isolated farmers were glad to see strangers. It was an opportunity to hear the latest news. Food, most often biscuits and molasses, was also offered if the family could afford to provide it. This was part of the hospitality and friendliness still prominent in rural Oklahoma to this day.

SETTLING IN

Dorm housing was very basic — two bunk beds to accommodate four students in a small room. The other piece of furniture in the dorm room was a small, one-seat study table. In most dorm rooms, there was a single window that remained open during the warm months of the year.

New students arrived at Langston with all the clothing they owned. This generally consisted of a pair of shoes, an extra pair of pants, a few shirts, several pairs of socks, underwear, and some kind of winter jacket. These were unpacked from a potato sack or some other type of bag. Only a few students had the luxury of formal travel gear such as a suitcase. Personal items, such as clothing and toilet articles, were stored in a large wooden locker that occupied one of the few free spaces in the room.

Most Langston students were from towns similar to Chandler — small and rural. Until the trip to Langston, many had never left the towns in which they were born. Learning how to use inside plumbing, live away from home, manage time, and resist the urge to go hunting or fishing at a moment’s notice, were only a few of many adjustments required of new students.

Thanks to Mrs. Sawner’s persistent efforts, the transition to college life was not very difficult for the Ellises and others who had attended Douglass School. Unfortunately, for some the adjustments were too great. After a few months, they dropped out of school and returned to the free, predictable life of their small communities.

THE WORK/STUDY PROGRAM

Students provided labor for most of Langston’s support services. This was done under a work/study program in which a small core of permanently employed professionals supervised student workers. More than 90% of the students participated in the work/study program.

Under the program, each student worked four to six hours per day in exchange for room, board, laundry, and tuition costs. In the 1930s, this was equivalent to about 17 dollars per month. Students worked in one of several areas: the dining hall, kitchen, laundry, grounds maintenance, repair service, a labor force supporting building and facility construction, the dairy, or at one of the many agriculture related facilities.

Students not enrolled in work/study programs, faced a major problem — finding food!! This was a significant challenge during the Depression. In many situations students dropped out of school simply because they could not feed themselves. Ora Ellis became a victim of this situation as we will explain later in this chapter.

THE FOOD!

An overweight student was seldom encountered at Langston. Those entering the school overweight were significantly slimmer within a short period of time. The food provided in the dining hall was just enough for survival. The most common foods were those harvested from the school’s student-run vegetable fields and dairy. The Ellis brothers often joke about a degree from Langston being one of the best weight loss programs available at the time. Jim Ellis remembers several times walking the 68 miles, to and from Chandler, “just to get some of Mama’s home cooking.”

Tables large enough to accommodate 12 students at one sitting were neatly arranged in the dining room. There were several shifts for eating, with each group of students being given a specific time to eat. Seating was on a “first come, first served” basis. As the tables filled, the dining room servers would bring sufficient food for exactly 12 people. The food was placed on the table in large bowls and passed from person to person. It was important that each person only took his or her fair share of food. This guaranteed everyone at the table would be fed. There were usually no second helpings.

A typical day’s menu follows: Breakfast — scrambled eggs with brains, sausage, toast, grits and gravy, and coffee or tea. Lunch — macaroni and cheese, hotdogs, and black-eyed peas. Dinner — chicken or pork, with vegetables and bread. The Saturday evening meal was the most notorious. The menu consisted of peanut butter and molasses with large biscuits. This meal was sometimes referred to as the “Saturday Night Special.” Peanut butter was well liked because portions could be saved and eaten later or shared with friends who did not have dining hall privileges. Saturday night social events often carried the smell of peanut butter eaten several hours before.

One alumni remembers an interesting incident when he entered Langston in 1938. Upon entering the dining hall for the first time, he found all seats were taken, with the exception of one chair at a table of upper class women. He hesitantly occupied the last chair at the table just as the servers were placing the bowls of steaming food before the waiting students. The girl at the head of the table immediately began passing the bowls to her right. She was careful to make sure the last person to receive the platter of food was the freshman who had just seated himself on her left. As she began passing the first bowl, she asked in a sarcastic tone, “How did this crab get in here?” “Crab” was the nickname given to freshmen by upperclassmen. One of the other girls at the table asked, “What Crab?” The response was, “That big black one sitting over there.” The banter among the upper class girls continued with more insulting comments, but no eye contact with the unsuspecting newcomer. The freshman said nothing and politely waited for the platters of food to reach him. Each platter was completely empty by the time it arrived in his hands. The last two persons sitting to the freshman’s left meticulously made sure the last piece or spoonful of each item was taken before it reached him. For the remainder of the meal, the upper class girls casually ate and conversed among themselves as if the freshman at the table did not exist. From then on, that freshman and all who had observed his plight, knew where not to sit.

THE ELLIS CHILDREN AT LANGSTON

Ora had an interesting beginning to his first short stay at Langston. In 1933, at the age of seventeen, Ora reported to Langston to register for the fall term. The first step was a personal interview with the University’s president. Early in the morning, Ora reported to the President’s office and stood at the end of a short line of students waiting to seek the president’s personal approval to enter the school.

When Ora’s turn came, he smartly entered the office with his hat neatly tucked under his arm. The president acknowledged his presence and continued reviewing the list of students on the desk before him. “Your name is Ellis, isn’t it?” he politely asked. Ora nodded his head affirmatively. “Don’t you already have some brothers and sisters around here?” he asked with a half smile (Cliff and Hasko were students and Jim had graduated the year before). Ora quickly replied, “Yes,” with growing confidence, as he knew the Ellises were well known for being excellent students. Ora quietly anticipated the next comment — approval of his registration for the fall term. Instead, the president smiled and replied, “We already have too many Ellises around here. You’ll have to wait until some of them graduate.” Ora stood still, shocked by the president’s decision. The next student was already entering the president’s office for his interview, so Ora had to leave without responding to his rejection.

Ora quickly found Hasko and Cliff to share the bad news and seek guidance. They met in the small loft above the cow barn in the part of the campus devoted to agriculture. As you stood in the loft, you could easily see and hear the cows eating on the ground level of the barn. The constant odor of cows and other livestock was always in the air. The loud munching sounds of feeding animals never ceased. Cliff worked in the agriculture department and the loft was his “office” and living quarters. The boys discussed Ora’s problem. Cliff and Hasko agreed to help. Ora would stay and attend classes despite the president’s decision. They would have to find a place for him to stay. He would not go back to Chandler!

To remain in the school without the president’s approval was possible in those days because there was no effective system to manage students. Anyone who desired to do so could attend a class and receive a grade as long as they fulfilled all class requirements. Ora’s big task was to avoid being seen by the president. Ora had saved $92.50 from three years working for the WPA. This money was used to rent a small room under a local store and to finance his studies. Cliff was able to help by providing a small amount of milk each day.

Despite the best support efforts of his siblings and friends, Ora’s resources were quickly exhausted. He dropped out of Langston after four months. Determined to get his college education, he returned in 1936 and graduated in 1940.

Ann, my mother, was the last Ellis to study at Langston. She began as a freshman in 1937 and in 1939, she married my father, Melvin R. Chatman Sr., a fellow student. Mom started her family in 1940 and did not return to Langston. In 1947, after divorcing my father, she returned to Langston to complete her undergraduate studies. My brother, Whit, and I accompanied her — we were six and seven years of age, respectively. She graduated in 1948.

Whenever I ask if someone knew my mother, if their response was yes, it would always begin with, “She was the most beautiful woman I have ever seen and she... ” I never noticed her outside beauty; she was always just plain old “Mom” to my brother Whit and me. We knew her beauty, but in a different way.

Mother was a warm and bubbling personality who always carried herself in a dignified and self-confident manner. She drew full attention whenever she entered a room. Her special talent was being able to listen to personal problems and share creative approaches for solving them. After a few minutes, new acquaintances became old friends. Friends tell wonderful tales about my mother and how she helped them through tough times. As they recall the special ways she touched them and made their lives happier, broad smiles quickly interrupt and stop their tears.

My mother loved my brother Whit and me and was dedicated to making us successful human beings. Her convictions were Bible based, with unshakable faith in doing the right thing, even if it was contrary to others’ opinions. In the mid-40s, what black woman with two young children would dare leave her husband?

In 1976, for some unknown reason, my mother was taken from us at the age of 56. It is difficult to understand the early departure of this beautiful woman. I am still very bitter about the matter, especially given that most other family members live to be 80 years old or older.

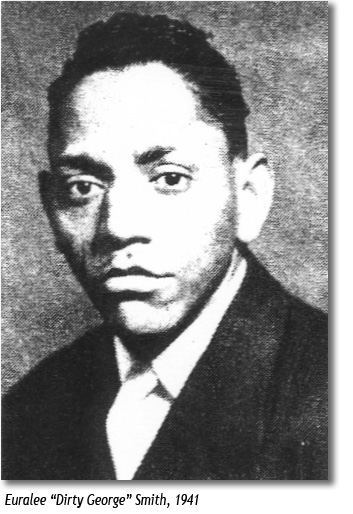

EURALEE “DIRTY GEORGE” SMITH

A number of interesting personalities populated the Langston campus. Euralee “Dirty George” or “De George” Smith attended the school in the late 1930s and early 1940s. He was one of the most famous of Langston’s “smile makers.” No one knows how he received his nickname.

Dirty George was the local “stop and shop” — open 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Operating from a carefully guarded closet in one of the dorms, he sold almost every item desired by his fellow students. His inventory included cigarettes (often sold individually), all types of clothing, canned goods, cosmetics, footwear, and bootleg whiskey. It was not uncommon to see a line of students waiting to sip a glass of “moonshine” whiskey smuggled onto the campus by the enterprising Dirty George.

He was an immaculate dresser who only wore clothes he had personally designed. George’s specialty was tailor-made clothing for both men and women. At the homecoming football game, he took great pride in being the last spectator entering the stadium. Dressed in a new suit made for the weekend, he would proudly walk to a place in the middle of the grandstand, strolling casually, recognizing friends, but allowing plenty of time for everyone to admire his latest creation. He sometimes disappeared just before halftime and reappeared in the second half in a completely new outfit.

To keep in touch with the entire student body, George had female students selling his wares in the girls’ dormitories. He had a large following of female students who not only admired his fancy dress, but also the suave and romantic manner in which he treated the ladies.

THE CONSTRUCTION AND DESTRUCTION OF MARQUESS HALL

Marquess Hall men’s dormitory was built in 1922 at a cost of $40,000. It was one of the many buildings constructed using student labor. The objective of the labor program was to not only provide housing for male students but also train them in construction industry skills. Construction using student labor was a very slow and arduous process. Each one of the student-constructed areas had to be carefully inspected by a teacher. During the construction of Marquess Hall there was concern about the overall strength of the building. It needed to be strong enough to resist the often violent Oklahoma weather. In their enthusiasm to meet the challenge of the weather, students constructed walls with several layers of brick. These walls were carefully built under the blazing Oklahoma sun. The finished product was a concrete, bunker-like facility that could have been used in a combat area. The efficiency of the students’ labors was not appreciated until 1972, when Marquess Hall was to be torn down and replaced by a newer and larger facility.

The first two contractors employed to destroy the hall withdrew from the contract because they could not tear down the “Marquess Hall bunker.” The solid construction of the building made its destruction by conventional means almost impossible. A third contractor was finally successful after bringing in special equipment to do the job.

I have one last chuckle on Marquess Hall. Students provided the labor for the maintenance teams that assured everything on Langston’s growing campus was functioning properly. There were teams assigned to every kind of task. Assignments to the maintenance and construction crews were part of the on-the-job training for students working in the industrial programs. Each one of the teams had a student team leader. The leadership positions were always reserved for juniors and seniors. “Big Red” was the leader of the plumbing repair team. He held the position because he was an upperclassman and not because he was the best leader. Red was appropriately nicknamed due to his red hair. His inability to properly repair most of the tasks assigned to his crew on their first effort was well known. They would have to be called back several times before a job was done correctly.

The original Marquess Hall building had running water but no hot water. The lack of hot water was not a problem in the warm months. Things were quite different during the winter when shivering students would dash in and out of the showers to avoid the coldness of both the shower and the shower room.

In the mid-1930s, funding was obtained to install hot water in all student dormitories. Big Red and his crew were given the installation task for Marquess Hall. They arrived early in the morning on the first day to begin work. Red was concerned because one of his grades would be based on how well he and his crew installed the hot water system. Within a week, Red and his crew proudly announced to the dorm supervisor that the job was done. He and his men immediately departed to celebrate completion of the installation, patting each other on the back for a job well done.

About two hours later Big Red was contacted in the campus union where the team was boasting about their accomplishment. In a very irate voice the dorm supervisor explained that he had received complaints from students all over Marquess Hall. They still did not have hot water. However, whenever students used the toilets they could feel hot air rising from the ceramic bowl. They also noticed hot steam spiraling from the toilet each time it was flushed. From this event Big Red reinforced his reputation for never doing anything correct the first time and earned a new nickname — “Hot Rectum Red.”

Ten of the 11 Ellis family members were students or staff members at Langston University. Only Whit Ellis Sr. had no Langston connection.

The Langston experience did several things for the Ellis family. First, it provided a good academic base to move ahead to bigger and better things. Second, it provided new knowledge about people and places different from the ones familiar to the family. This occurred at a time when most black citizens spent their entire lives in the counties where they were born. They had limited contact with people different from themselves. This exposure to new people and places was very helpful when family members left Oklahoma. Third, it established a large group of life-long friends. These friends became part of a “helping hand” network important as each member of the family grew into adulthood and departed from Oklahoma.