|

JAMES RILEY

On December 12, 1844, James Riley, my mother’s maternal step-grandfather, was born in New Orleans, Louisiana. Our family has always referred to him as James Riley or Grandpa Riley. At five years of age, James was bought by a Mississippi plantation owner living near the Louisiana border. By his early twenties, the tall, wiry young man was in excellent physical condition. Throughout his life, James Riley maintained a slender frame and wrinkle-free face that appeared much younger than his age. James Riley spoke with the Cajun accent of Louisiana. He spoke of “gawd,” instead of God, and “aiss,” instead of as, his accent clearly labeling him an outsider.

Grandpa Riley was a “smile maker.” Smiles quickly blossom on the faces of listeners whenever his name is mentioned. This was usually followed by laughter and humorous comments about his exploits. James Riley was quite a character, warmly loved and respected by all who knew him.

MIGRATION FROM NOVA SCOTIA: A RUDE AWAKENING

We believe Grandpa Riley had Canadian origins. He often commented that his grandfather’s family came from a very cold place north of the United States and that they arrived in this country by boat. We believe he referred to a Canadian area near the town of Digby, Nova Scotia. French traders probably brought James Riley’s ancestors to Nova Scotia in the mid-1700s. We believe they were not slaves, but settlers, brought as manpower to develop the rugged northern frontier. It appears there was significant intermingling of the races, and marriage between whites and blacks was not uncommon. Under French cultural and political control, black citizens of Nova Scotia lived comfortable lives.

Once Canada became part of the British colonial system, things began to change. In the early 1700s, France initiated an effort to expand its influence in Canada. France and Great Britain fought a low-key war over French colonization during most of the 1700s. This struggle ended in 1783 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Under the treaty, Great Britain formally declared sovereignty over the United States (formerly its thirteen colonies) and firmed up the boundaries of its authority in Canada. The ripple effect of this treaty spread across North America and resulted in new opportunities for people living in Nova Scotia. One of the most important was the opportunity for French-connected Canadians to migrate to the United States.

James Riley’s grandparents were members of a large family bearing the family name Duprée. After signing of the Treaty of Paris, the family of approximately 60 members chose to migrate to French settlements in what is now the Louisiana–Mississippi border.

The Duprée family members who moved to the South exhibited widely different racial characteristics. Some were light-skinned with straight hair and appeared to be white. In Nova Scotia, all family members were treated equally, regardless of their physical appearance. Once the family arrived in the United States, the darker family members, including James Riley's parents, faced a rude awakening.

Cotton production in Louisiana and Mississippi was dependent upon slave labor. The light-skinned Duprée family members were accepted as “Cajuns” and enjoyed the many privileges of their white neighbors. One was the right to own slaves. The family patriarch, “Uncle Duprée,” a light-skinned black man, quickly declared himself a slave owner and assumed control of his dark-skinned relatives. Uncle Duprée not only became master of his dark-skinned family members, but also a cruel, unfair slave owner whose abuses far exceeded those of white slave owners.

BORN INTO SLAVERY

While some accounts indicate a later date, it is assumed that James Riley was born into slavery in New Orleans, Louisiana, on December 12, 1844.

In an affidavit dated November 21, 1913, Grandpa Riley stated, “I was sold as a slave at five or six years of age, and have recollection that my parents bore the name of Harrison.” In 1939, the Riley family submitted a claim to the U.S. Army for compensation of Grandpa Riley’s funeral expenses. The paperwork lists Grandpa Riley’s father as Jack Laughton and his mother as unknown. There is no further mention of James Riley’s parents in any other documentation.

While a slave, James Riley may have married and fathered several children. After his death in 1938, Ann Riley mentioned the possibility of James having a prior family. It is not clear where she obtained this information.

Grandpa Riley’s life, and that of his family, was typical for slaves in the mid-1800s. The men spent long hours under the blistering Mississippi sun picking cotton, plowing fields, taking care of livestock, repairing equipment, and performing whatever jobs the “masters” assigned them. Slave women cared for their own children as well as those of their masters. They cooked, washed, cleaned, and attended the sick and elderly. Despite working hard, they were often treated like farm animals. In most cases, masters had no desire to educate their slaves. “All they need to know is how to pick cotton and plough fields,” was the common refrain in response to the question of educating slaves.

One of Grandpa Riley’s early memories is worth sharing. As a young slave, James Riley was not allowed to learn to read and write. However, he often played with the master’s children, who were relatives and attended school. One day he came upon one of the Duprée children reading a book. Noting the letters on each page, he asked, “What are all of those black things?” The Duprée child responded, “They are little niggers. They will tell you a lot if you learn how to listen to them.”

THE ESCAPE FROM SLAVERY

While still young, James Riley reached a point where he could no longer bear the drudgery of slavery. Near the Civil War’s end, then twenty-year-old James joined several other men and women to escape from slavery.

No detailed plans were made. The matter could never be openly discussed. Anyone hoping to escape feared the “paddyrollers.” As Grandpa Riley explained it, paddyrollers were teams of men organized to prevent slaves from escaping and to recapture those who did escape (Paddyroller was one of many mispronunciations of the word “patrol” or “patroller” often spoken among the slaves). The plantation owners organized the teams; slaves were sometimes members. Once a slave escaped, the paddyrollers functioned as bounty hunters, well paid for capturing runaways. In addition, paddyrollers often brutally punished slaves they captured.

The ultimate escape plan was agreed to during a short, secret meeting behind a barn. Under cover of darkness, and carrying with them a few personal items, food, and water, the group left the plantation. The paddyrollers quickly unleashed their dogs and began searching for the group. The escape quickly became an endurance race between the slaves and the bounty hunters.

The paddyrollers, mounted on horseback, and the small group of freedom seekers, were never far apart. James Riley and his fellow slaves used tricks to confuse the pursuing dogs. They followed streambeds and doubled back over their own tracks. At times they threw pieces of raw meat to distract the dogs. As they continued north the baying hounds could be heard constantly just a short distance behind. By the time the slaves reached the Mississippi River and freedom, their clothes were in shreds from traveling through thick underbrush. Several people were naked and bleeding. All were exhausted and on the verge of collapse. Two members of their group disappeared. It is not known whether they were captured or continued their flight in another direction.

With their last bit of remaining strength, relying upon the stronger to assist the weaker, the group swam across the Mississippi River. On the other bank, the former slaves exchanged quick goodbyes and parted. They were never to see one another again.

By himself, James Riley headed north toward a Union Army encampment blockading the Mississippi River. Even before his escape, he had planned to join the Union Army on the northern side of the river.

In the 1920s, James Riley returned to Mississippi to find his former masters and to exact revenge for the injustices he’d suffered under their control. Grandpa Riley’s wife, Ann, encouraged the trip. The search proved fruitless. All traces of his past slavery had vanished. He found nothing of his own family or that of his former masters.

We believe that Grandpa Riley’s determination, discipline, and frequent distrust of white people were deeply rooted in his experiences as a slave in Mississippi. Those experiences left a harsh and permanent scar on his personality.

THE MILITARY YEARS

From March 1865 to November 1874, James Riley served in the U.S. Army. He began his military career near the end of the Civil War. On March 21, 1865, James joined his first unit, the Union Army, Company B of the 81st Infantry Regiment (volunteers). Grandpa Riley adopted the name of the general he served as a personal orderly, James Reilly. Before that time, he was probably called by the names most convenient to his slave masters: Boy, Black Jim, or Nigger Jim. It is unexplained why he decided to spell his name “Riley” instead of “Reilly.” His grandsons smile and explain, “It is a simple spelling error. Grandpa Riley was never too handy with the pen and pencil.” Few details about the first short period of Grandpa Riley’s military career are available, with one exception, his presence at General Lee’s surrender in 1865.

General Lee’s Surrender at Appomattox As Told By Grandpa Riley

Grandpa Riley claimed to be at Appomattox with General Reilly on April 9, 1865, when General Lee surrendered to Union forces under General Grant. He recalled the event as one of great splendor. In Grandpa Riley’s telling of the events, General Lee entered the crowded area designated for the surrender. Four calls on a bugle announced his arrival. This was followed by someone shouting, “Attention world! Attention world! Attention world! Attention world! General Lee has arrived to surrender.”

General Lee dismounted his horse, unsheathed his sword and handed it to General Grant. In a gesture of respect to the Confederate leader, General Grant immediately returned the sword to General Lee and requested that he remount his horse. He was not to be treated as a prisoner of war. The ceremony ending the Civil War continued in a dignified manner.

(NOTE: James Riley’s account of how he obtained his last name and the details of the Appomattox surrender of General Lee differ from other accounts. Further research is needed to clarify several issues.)

The Buffalo Soldier Period

James Riley was discharged from his initial enlistment in the Army on October 22, 1866. On that same day, he reenlisted and was assigned to Company C, 339th U. S. Infantry. On April 20, 1869, because of a consolidation, he was reassigned to Company A of the 25th U.S. Infantry Division. He served in the 25th until his discharge on November 9, 1874, at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

The 25th Infantry Division was one of the units known as “buffalo soldiers,” the nickname given by the Indians to black soldiers serving in the western frontier of the United States from about 1866 to 1891. It is believed the Indians gave the black soldiers this nickname because their hair was reminiscent of the rough, hairy mane of the buffalo. It was also in recognition of the black soldiers’ outstanding ability to cope with life on the rugged frontier. Buffalo soldiers were assigned tasks such as construction of military forts and housekeeping chores, mainly in the states of Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, Arkansas, and all of what was then known as the Oklahoma Indian Territory. James Riley mentioned that he assisted in the construction of Fort Sill and Fort Caddo in Oklahoma. After the Civil War, the government used the army to perform many functions in the so-called “uninhabitable lands” of the west because life in these areas was primitive and hazardous.

The colored soldiers were often given tasks undesirable to white military units. A major example was acting as a police force in the Indian Territories and controlling settlers who attempted to illegally establish homesteads on Indian land.

Ambushed

On one occasion, James Riley’s small patrol spotted what appeared to be a group of Indian women drinking at a water hole. The soldiers looked upon this as an opportunity to obtain long desired female companionship. They confidently approached the water hole only to be ambushed by skillfully disguised Indian braves. A short, but ferocious fight followed, then the Indians quickly retreated, leaving several of the soldiers wounded.

Grandpa Riley had been severely slashed in his gut and left on the ground with his intestines exposed. In great pain, and holding his intestines in his hands, he stumbled to his bivouac area about a mile away. He fell to the ground many times during that painful journey. The medics poured water on his protruding intestines to wash away the dirt and sand accumulated from his many falls, placed the intestines back inside his body, then closed up the wound with thread used to mend clothes. This experience left a thick, ugly scar across the entire lower part of Grandpa’s abdomen — a permanent reminder of his military years.

The Stolen Boundary

Circa 1870, Grandpa Riley was assigned to the area that eventually became Chandler, Oklahoma. In a 1938 interview published in a Lincoln County newspaper, he described his first look at what was to become Chandler. “You could have passed Chandler without knowing it was there. There was nothing but rolling hills, with no people except for a few Indians here and there.”

James Riley was a member of a group of soldiers that planted a line of trees, north and south on what is thought to now be Post Road. The road runs north and south of Route 66, about two miles west of the current Chandler city limits. They planted trees at what was officially designated as the western boundary of the Sac and Fox Indian territories. When the first land rush took place in 1891, unscrupulous land surveyors moved the boundary east, thereby robbing the Indians of several miles of prime land.

Many years later, as he visited friends, James Riley would cross the tree line boundary in a horse and buggy. Each time he passed, he would recount the “stolen boundary” incident to whoever was accompanying him. Part of the tree line boundary can still be seen at the Chandler city boundary line, just northwest of the intersection of Post Road and Route 66.

The Massacre of Women and Children – A Change of Heart

One event in the late 1860s drastically changed James Riley’s opinion of the Army. Grandpa tells that, as usual, the black military units were given the nasty jobs unwanted by the segregated white units. Company C of the 25th Infantry, his unit, was given the task of cleaning up a battlefield after a great U.S. Cavalry victory. It may have been one of George Armstrong Custer’s well-publicized adventures — possibly the Battle of Washita.

Grandpa’s unit was told to bury the bodies of the many “wild” Indian braves that perished during the skirmish. As the burial detail entered the battleground, they were shocked to discover that the fallen Indians were women, children, and old men who had been brutally slaughtered by the U.S. Calvary. Many of the children’s skulls had been crushed by large rocks, and the rocks, still red with blood, were strewn throughout the battlefield.

The soldiers were horrified at the spectacle before them. There was not a dry eye in the group. Some wept openly, while others shook their heads in disbelief at what they saw. Some knelt and prayed while others stared in silence.

The black soldiers had reason for this strong reaction. After years of living among the Indians, they had developed a special respect for them. Many of the soldiers were former slaves who had found freedom and warm hospitality with the Indian tribes. Some were of mixed black and Indian ancestry. For many, the brutal slaughter brought back terrible memories of slavery and the treatment of black people after slavery was abolished.

For Grandpa Riley, this single incident completely changed his image of the U.S. Military. He no longer desired to be associated with anyone who would commit such crimes.

The Military’s Lasting Influence

On November 9, 1874, at the age of 30, James Riley resigned from the U.S. Army and became a civilian. Although he felt compelled to resign, he had truly enjoyed most of his military experience. The military lifestyle influenced Grandpa Riley for the remainder of his long life. He loved discipline and having things kept in an orderly fashion. His clothes were often “thread worn” and patched, but always neatly pressed and tailored.

Grandpa Riley never forgot the military manual of arms. The manual of arms was a combination of marching steps and drills done with a rifle. Even at more than 80 years of age, he would call all 12 members of the Ellis family to attention as he performed the manual of arms. In front of the group, he would smartly prance, shout the cadences, and perform the weapon’s movements using a broom to represent his rifle. As they stood at attention, the family would struggle to conceal their amusement. As his grandchildren became of courting age, the military marching sometimes became a point of embarrassment. Grandpa Riley often called the family to attention when a visiting boyfriend or girlfriend was present. The visitors usually stood in shock as 80 year-old Grandpa Riley marched around the living room with a broom smartly slung over his shoulder, shouting out various commands.

The 75th Reunion of the Battle of Gettysburg

One of Grandpa Riley’s most exciting military adventures occurred at the 75th Reunion of the Battle of Gettysburg at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. All surviving Civil War veterans were invited, even those who did not participate in the actual Battle of Gettysburg.

From June 29 to July 6, 1938, the U.S. government and the State of Pennsylvania sponsored the reunion. Each Civil War veteran was authorized a chaperon at government expense. Chaperons and other support personnel outnumbered the veterans by a margin of two to one. Some of the chaperons were full-time doctors and nurses.

James Riley, at the age of 94, was one of 1,850 ex-soldiers (all 90 years and older) from both sides who attended the event. Grandpa Riley was the only black veteran among the group of 63 representing Oklahoma. According to Francis Ellis, Grandpa’s grandchild who accompanied him, they did not see more than four or five other black veterans at the reunion. Using a 99-cent camera purchased specially for the event, Francis took pictures at the reunion.

Grandpa Riley described the reunion as the most important event of his life. The old veterans were housed in tents. They relived and refought the battles of the war. There were many comical scenes as the old soldiers hobbled in and out of their tents, argued, and joked with each other. There were mock battles and continuous debates over “who defeated whom.” The reunion, supported by a great deal of liquor and food, was a splendid success. James Riley received a great deal of local media coverage, with his picture appearing several times in local newspapers.

In one article, the reporter casually referred to James Riley as “the old darky.” Several days after his return from the reunion, the same reporter arrived at Grandpa Riley’s farm for a follow-up interview. Not realizing the insult he’d committed, he knocked on the front door of the house. Grandpa Riley arose from a nap in his rocking chair, answered the door, and upon seeing the reporter, flew into a rage. James Riley threatened the reporter several times, telling him what he would do if he ever saw his “frail ass” on his property again. The shocked reporter retreated to his car and quickly departed with our 94-year-old grandfather in hot pursuit. When the car was down the road several hundred feet, Grandpa Riley remembered his shotgun and ran back into the house to find it. He reappeared with the shotgun, shaking it at the car, and shouting obscenities in a heavy Cajun accent that only he could understand. He paced back and forth in front of the farmhouse for several minutes, then returned to his favorite rocking chair to continue his nap. The reporter was never seen again at the Riley farm.

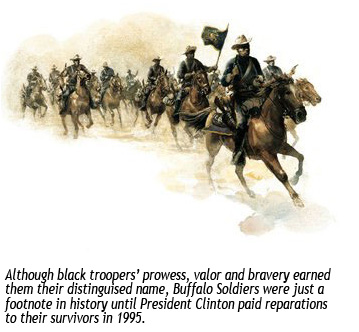

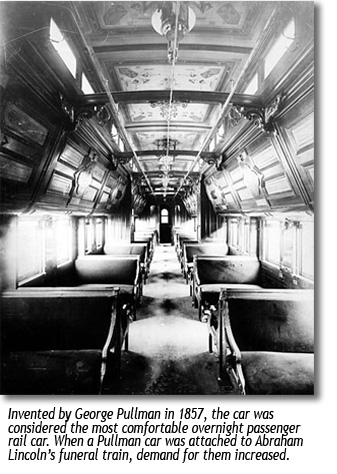

James Riley, the First Black Oklahoman to Ride in a Pullman Sleeping Car

There is another significant event related to the Grandpa Riley’s participation in the Gettysburg Reunion. We believe he was the first “colored” Oklahoman to ride in a Pullman Sleeping Car.

Grandpa Riley’s Pullman Car Ticket

Grandpa Riley received the Gettysburg reunion invitation several months before the event. With great excitement, the hosts were informed that he planned to attend. Grandpa Riley would be the only veteran attending from Lincoln County and the only black Civil War veteran from Oklahoma. Several weeks later he received a large envelope of reunion materials. In the envelope were a schedule of events, literature about the area, information about the person authorized to accompany him, and other details. The envelope also contained two train tickets clearly marked “Pullman Car.” This was a pleasant shock since Oklahoma law required colored persons to ride in a segregated, less comfortable section of the train. The Pullman Cars were always reserved for white passengers.

Pullman Cars were specially designed to accommodate comfortable sleep on long train rides and were outfitted with numerous sleeping berths as well as two luxurious drawing rooms in which the wealthiest passengers could ride and sleep. Ticket holders for “sleeper berths” also held passenger seats on the train. Accommodations in the Pullman Cars were prestigious and costly. However, black people who could afford this luxury were forbidden to utilize it. Grandpa Riley went to the railroad station to verify his seat and inform the railroad that his grandson, Francis, would accompany him. When the clerk noted the ticket voucher was marked Pullman Sleeper, he told Grandpa Riley: “This is Oklahoma, and black people don’t ride in Pullman Cars.” He refused to issue the ticket authorized by the government. Grandpa Riley returned home and shared details of the incident with other members of his family.

The family contacted Mrs. L. Lena Sawner, principal of the local high school for black students, and she called one of her many contacts in Washington, D.C. Grandpa returned to the station the next day, and the station master, obviously displeased, disbursed two tickets for one of the Pullman Car’s exclusive drawing rooms! The 62 white Oklahoma Civil War veterans were given regular Pullman accommodations. The drawing rooms were private, enclosed compartments where the Riley group could travel without being in contact with the other passengers. James Riley was still segregated, but in the best part of the train!

The train left Chandler on June 27, 1938. Accompanied by Francis, Grandpa Riley was aboard, attired in a custom-tailored three-piece suit and a new top hat bought for the special occasion. Several times before the trip, he had proudly modeled the new clothes for friends and relatives.

Grandpa Riley occupied the seat closest to the window and made it a point to be highly visible as the white passengers boarded the train. He placed his face as close to the window as possible, politely tilting his hat and smiling at each white passenger entering the train. “What in the hell is that nigger doing in there?,” was the question silently mouthed by the white passengers outside the window as they boarded the train. Grandpa Riley thoroughly enjoyed the ruckus he was causing. The obscenities motivated him to new heights. The more he received, the bigger his smile grew and the more pronounced became the tilting of his new top hat.

To reduce the need for James Riley and young Francis to mix with the white passengers, the railroad provided food service to their drawing room. The black porter bringing the food always arrived with a smile. He took pride in serving the black gentlemen in the drawing room. At the end of the three-day trip, he refused a tip. The porter was honored to contribute to Grandpa Riley’s triumphant ride in the Pullman car.

James Riley’s military service became an inspiration for the service of other members of our family. With the exception of the Spanish-American War, James Riley, or one of his descendants, has participated in every major United States war effort prior to 1980.

|

List of Riley Descendants Participating in U.S. Wars:

|

|

|

|

|

Civil War (1861-65):

|

Sergeant James Riley

|

|

WW I (1914-18):

|

Winfield Riley

|

|

WW II (1939-45):

|

First Sergeant Harold Neal

|

|

|

Captain Frank Ellis

|

|

|

Master Sergeant Hasko Ellis

|

|

|

Sergeant George Ellis

|

|

|

Private Anderson Field

|

|

Korean War (1950-53):

|

Captain Harold Neal

|

|

Vietnam War (1959-75)

|

Lieutenant Colonel Harold Neal

|

|

|

Captain Mel Chatman

|

The Final Road to Chandler

Despite his rather comical demeanor, Grandpa Riley was a rugged frontiersman, ready to stand up against any man at any time. A double-barreled shotgun was his constant companion, and there was no question in anyone’s mind that he would use it if necessary.

After his military discharge, Grandpa Riley drifted from place to place, then, in 1884, he met his match. This happened when he married Ann Neal Thomas in Dallas, Texas. While he continued to stand up to everyone else, Grandma Riley completely tamed the rugged frontiersman. Most arguments ended with Grandpa walking away and mumbling to himself. We are not aware of him ever winning a battle when dealing with his wife.

Marriage began a new era in the life of James Riley. At 40, he was a black man vested with extraordinary knowledge from a life filled with adversity and adventure. He had endured the horrors of slavery and escaped. He had lived with the Indians, worked in several states, interacted closely with white people in non-slavery situations, and had first-hand experience with the brutality of war. His extensive life experiences were important for the role he would play in the Ellis family history.

Much of Grandpa Riley’s military service was in Oklahoma, where he developed a special liking for Chandler, the people, and the location. In 1890, James Riley, his wife, and four children would return to Chandler to start a new life. The main part of our story is what occurred after his return to Chandler and his step-daughter, Maggie, began her family.

ANN NEAL

On June 29, 1862, Ann Neal was born a slave in the tidewater country of Virginia. Much like her husband, mentioning Ann’s name brought smiles to the faces of all who knew her. During her long life, she would also call herself Anna and Annie. Noted for frankness, she said whatever she thought whenever she thought it and to whomever she pleased. Ann Riley was especially known for commenting on the church and its members in the middle of the Sunday morning sermon. She played a major role in the development of the Ellis children. We all called her Grandma Riley.

Grandma Riley passed on very few childhood memories. The scanty details she shared were based on stories told by her older relatives. One of them was the story of her family’s relocation. In 1863, her slave masters joined a group of like-minded white farmers concerned that the outcome of the Civil War would result in liberation of slaves. They feared the loss of their most prized possessions: free manpower to toil fields and make their lives comfortable. The group conjectured that, regardless of the outcome of the war, they would have a better chance of maintaining the old slave system if they were located in Texas. They decided to move their families and slaves to Texas.

The trip began with roughly 200 slaves crowded into 24 wagons. The journey took approximately two years and involved many stops at temporary locations before arrival at their final destination, an area now called Love Field, in modern day Dallas, Texas. Six of the families — named Neal, Peace, Bonner, Hill, Watson and Fields – remained there as a group while the others followed their masters to other parts of Texas. Regrettably, there are no details about Grandma Riley’s early childhood in Texas.

Ann Riley was married at least once before she married James Riley, but our information is inconsistent. Grandpa Riley’s Army pension documents tell us that, before marrying him, Ann Riley married John Thomas in 1879. He died several years later. There is no further mention of him.

According to Ann Riley’s first child, Maggie Ellis (born in 1880), her father was a wagon repairman whose name was James Bouldukes. While working, he was killed by a falling wagon when Maggie Ellis was very young. She recalled her father being a tall, light-skinned black man with red hair. Maggie believed her father was black and half-Irish. She was also told that he had something to do with Civil War prisoners. We realize that this time period, 1879-1884, leaves the reader with a number of questions we are unable to answer at this time.

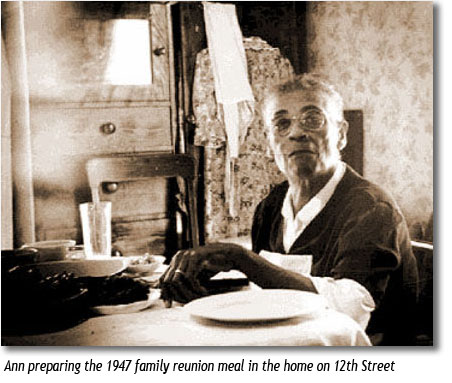

Ann Neal married James Riley in 1884. As previously mentioned, Ann Neal brought a four-year-old daughter, Maggie, into the marriage. Ann and James had three additional children: Polly, born June 30, 1886, Winfield F., born May 31, 1888, and Zodie, born June 8, 1890.

Ann Riley became famous for many things. One was her ability to cook. She used an old wood stove to prepare meals. Gracefully moving around the kitchen, she would hum or carry on an uninterrupted conversation with one or more of her grandchildren as she prepared a meal. Within an hour, and as if by magic, she could complete a tasty four-course meal for ten people and have it steaming hot on the table, ready to eat. Her most noteworthy accomplishment was the annual Christmas dinner at her farm. The event was an all-day affair attended by all of her family and relatives on good terms with her at the time. Preparations began some three months in advance. For three days prior to the event, Grandma was occupied full-time with the Christmas dinner activities.

Maggie Ellis frowned on the use of the word “nigger.” Although mostly outlawed in the Ellis house, Grandma Riley used the word liberally, frequently using the forbidden slang word to comment on the behavior of black relatives, friends, and members of the community when their actions did not meet her high expectations. She was often heard commenting, “Just like a bunch of niggers, always trying to ....” When extremely perturbed at Grandpa Riley, she would refer to him as “that ole nigger.”

Grandma Riley was a God-fearing woman. The church was an important part of her life. She had a very special relationship with God and those who represented Him. I’ll relate a few of the events demonstrating this special relationship.

The Too-long Sermon

Ann Riley cherished the friendship of the local minister. However, she was well known for commenting on his church and its activities, even when that included disagreeing with the preacher right in the middle of his sermon. After being interrupted by Grandma, the preacher would pause for a moment, then politely respond, “Thank you, Sister Riley.”

Children attending church would wait anxiously to laugh and snicker at Grandma’s spontaneous comments. The children were especially pleased one day in the middle of an excessively long sermon. After more than an hour and a half of what appeared to be an endless presentation, Grandma Riley reached the end of her patience. The signs were obvious — she began shaking her head in a slow, negative manner at each comment coming from the pulpit. At the same time, she tapped her foot in quick beats on the floor as does a restless child. A deep breath was taken, and in her loud raspy voice she said, “Why don’t you shut up before you start lying.” Her challenge was followed by the muffled laughter of all the children sitting of the church. The preacher paused for a few seconds, then concluded the sermon.

Grandma and the “Happy” Lady

In another situation, a seriously overweight female member of the church developed a weekly ritual of “getting happy” in the middle of the Sunday morning service. At the height of this emotional event, she would go far beyond what was expected of one who was touched by the “Holy Spirit,” and run around the church, yelling and screaming at the top of her voice, then jump up and down out of control.

On a hot and humid summer day, when she reached her emotional climax, the woman leaped, then stood on the empty seat next to Grandma Riley. She jumped up and down two final times. The sheer weight of her huge body bounced Ann Riley and the two children sitting next to her about six inches in the air. They returned to the seat with a painful, simultaneous, “thud.” The woman then regained her composure and returned to her seat, exhausted and perspiring. As she moved away, Grandma Riley commented: “Big, fat ass women ought to sit down and shut up.”

Everyone in the church heard Grandma’s commentary. The children laughed quietly while the congregation sat in stunned silence for about two minutes. The preacher finally broke the silence. “Thank you, Sister Riley, for your comment.” Most of the adults covered their faces with handkerchiefs or fans to hide the smiles and expressions of approval for Grandma’s remarks. Others in the church nodded in agreement as they said, “Amen!”

“Walk in My Footsteps”

It was a proud moment for Grandma Riley when her grandson, Ora Ellis, joined the church at the age of 12. With the entire congregation looking on, she walked proudly in front of Ora, up the aisle toward the pulpit. After taking three long, exaggerated steps, she looked over her shoulder at Ora and said with a big smile, “Walk in my footsteps because I am a Christian.” Recalling this moment at family reunions always evokes fond laughter.

As Grandma Riley grew older she would talk to herself, especially, if something disturbed her. Sometimes, after an unpleasant exchange with a neighbor, she would walk around the house mumbling to herself for several days. When tired of mumbling, she would hum her favorite gospel hymn. During the most upsetting moments, Grandma would hum and talk to herself intermittently. Everyone knew she was better left alone during these periods.

“Inside and Outside Niggers”

Grandma Riley seldom talked about the Civil War period. However, there was one of her mother’s stories she repeated quite often. Ann Riley, like her mother before her, was not afraid of going against “the system.” According to Grandma Riley’s mother, slaves were divided into two classifications: “Outside niggers” were slaves who worked outside the master’s home in the fields, workshops, and livestock areas. Without permission, they were not allowed inside the master’s house.

“Inside niggers” were specially chosen slaves serving the master and his family inside the main house. Owners would try to select the slaves most loyal to the family for inside positions. Inside niggers were the most trusted slaves, receiving the best of everything — food, clothing and access to the master, among other benefits. In many situations, the honored inside nigger positions were passed down among family members from one generation to the next.

One important point: inside niggers were expected to act as spies, keeping the master informed of all that went on among the slaves. Informing the master of other slaves’ plans to run away was a key aspect of this spy role. Informing the master of an escape plan usually resulted in quick capture and harsh punishment of those seeking freedom. Harsh punishment could mean sale to another slave owner, permanent maiming, or even death.

Grandma Riley’s mother was similar to her daughter, strong-willed and quite outspoken. Also, like her daughter, she was very perceptive of all that went on around her. The master and his family quickly recognized Grandma Riley’s mother’s sharp mind, ability to manage several tasks at the same time, and overall effectiveness as a worker. They continuously requested that she work inside the main house. At the same time, the family had a longstanding rule: only those who desired to do so should work inside the main house. Each time she was asked, Grandma Riley’s mother politely responded that she was honored for being considered by the family but was much happier working outside in the fresh air. Her response masked the deep hatred she held for the master, his family, and the slavery system they perpetuated. One generation later, these feelings surfaced with great intensity in the personality of her daughter, Ann Riley.

The serious side of Grandma Riley’s personality was respected by all who knew her. She was the town’s leading proponent of hard work, honesty, self-respect, and self-improvement. Ann Riley demanded high results from herself, as well as from all her children and grandchildren. In retrospect, some 50 years after her death Ellis family members recall Grandma Riley’s demands as difficult but never unfair. They were always attached to respect, dedication, and love. Ann Riley practiced what she preached, and her word was her honor!

Anne and James Riley were the roots of the Ellis family tree. Whit Ellis’s family, with the exception of a few well-spaced visits by Whit’s older brother Frank, had no contact with the children as they grew up. The Rileys were too tough, determined and very sincere role models who, in their own special ways, greatly influenced each member of the Ellis family.

|